Hard myths to (not) keep Singapore going

-

Lim Chin Siong vs Lee Kuan Yew: The true and shocking history

Part I: Our man

08 Jul 07

"The men who led Singapore to self-government and independence were swift to produce an authorized version of their struggle…,” historian T N Harper observes, "it began with Lee Kuan Yew's dramatic broadcasts as Prime Minister on Radio Malaya in 1961. The plot and the moral of this story are clear: by the political resolve and tactical acumen of its leaders, the fragile city-state weathers the perils of a volatile age and emerges into an era of stability and prosperity."

However, much to the discomfort of the Minister Mentor who hitherto has had a relatively free reign in portraying "the period as one in which Lim Chin Siong and the left were outmanoeuvred by the tactically more astute Lee Kuan Yew," Harper cautions that "authoritative new archival research sheds new light on the high politics of the period."

In other words, Lee's bravado with which he presently speaks covers up much that took place during those years.

In truth, Lim Chin Siong's fate was sealed right from the very beginning by the power of the British colonialists – and not Lee Kuan's political prowess.

At that time British authorities were already devising ways on how to stop Lim's ascent in Singapore's politics. Southeast Asia historian, Greg Poulgrain, writes that "In the Public Record Office in London are some of the observations and stratagems pursued by both the Colonial and Foreign Office – revealed now more than thirty years after the events – on how to deal with this rising star, Lim Siong Chin."

With Singaporeans becoming more educated and the advent of the Internet, events surrounding the heroics of Lee and his PAP during the period of independence and merger with Malaya "no longer looks so unilinear and uncontested."

The emergence of Lim Chin Siong

Harper recounts the "meteoric" rise of Lim Chin Siong as a student and trade union leader in the early 1950s who was at the heart of the anti-colonial politics that had erupted all over Asia following World War II.

By unifying the labour movement and galvanizing the overwhelmingly Chinese-speaking electorate through his formidable oratorical skills (he once told his massive audience: "Saya masuk first gear, lu jangan gostan!" – "When I go into the first gear, don't you go into reverse!"), Lim captured the attention of the masses.

And Lee Kuan Yew's too. This led to an association between the two men and the subsequent formation of the PAP. The anglophile Lee (Harry, as he once wanted to be called) saw the power of his younger Chinese-educated comrade.

Even within the PAP, "Lim eclipsed Lee Kuan Yew and other leaders in the popular following he commanded..."

But in his memoirs, The Singapore Story, published in 1998 Lee Kuan Yew condescendingly described Lim as "modest, humble and well-behaved, with a dedication to his cause that won my reluctant admiration and respect."

The truth is that Lee didn't have much of a choice. Lim Chin Siong was at the front, back and center of a political movement that commanded national attention. From all accounts, Lee would have been marginalized if his parasitic instincts had not been so acute.

Popular as he was locally, Lim Chin Siong did not confine his politics to within Singapore. Despite British efforts to isolate the island from anti-imperial movements that engulfed much of Empire, Lim would draw inspiration from liberation movements elsewhere in Africa and Asia.

His speeches in the early 1960s repeatedly made reference to events in the colonial world as well as to South Africa, Korea, and Turkey. This sense of internationalism had a "deep resonance" in Singapore.

The colonial government countered by censoring imported reading material. "This," writes Harper, "would continue, even intensify, after self-government as the PAP government increasingly saw itself as pitted against what Lee Kuan Yew was to term the ‘anti-colonialism' of global liberation movements."

In other words, Lee was not the hero who led the fight for Singapore's freedom. This might come as a shock to some but as declassified documents reveal, it was Lim Chin Siong who insisted that Singaporeans' freedom and independence were not for compromise.

It was also "what really caused the British authorities to consider [Lim] such a threat."

The talks collapse…

When David Marshall became the chief minister after his Labour Front won the elections in 1955, he organised a delegation to London the following year to negotiate independence from the British. Marshall included both Lim Chin Siong and Lee Kuan Yew in his team.

The chief minister fought hard, some say too hard, to wrest power from the British in the internal affairs of Singapore. He opposed Britain's power to appoint the police chief who in turn had power over the Special Branch, as it was then known. It was the Special Branch that gave the authorities the power of detention without trial.

The idea of retaining the power of internal security whilst granting self-government, Marshall accused the British, was like serving "Christmas pudding and arsenic sauce."

Lim Chin Siong supported the chief minister on this and demanded a constitution that transferred power to the local government with only defence and foreign relations left in British hands.

The British refused the demand and the talks collapsed. Marshall returned to Singapore frustrated and, amidst condemnation by Lee Kuan Yew, resigned as chief minister.

...Lim Chin Siong is detained…

Lim Yew Hock took over the position and led another visit to London the following year, which again included Lee Kuan Yew. But this time, Marshall and Lim Chin Siong were not part of the negotiating team.

More accurately, Lim Chin Siong could not go because Lim Yew Hock, as chief minister, had placed him under arrest, ostensibly for instigating a riot.

The episode began when Chief Minister Lim closed down a Chinese women's group and a musical association. A week later, he banned the Chinese Middle School Union which provoked further unhappiness with the locals.

Undeterred he arrested Chinese student leaders and shut down more organizations and schools, including the Chinese High School and the Chung Cheng High School. Given the already tense situation between the Chinese-speaking people and the colonial authorities, this was a highly provocative act.

At that time any Singaporean leader worth his salt could not have sat by idly. And so Lim Chin Siong came to the fore and spoke up for the students. The late Devan Nair, former Singapore president, joined in.

A 12-day stay-in was organised at one of the schools and Lim Chin Siong was scheduled to speak at a nearby park one evening.

It wasn't long before the police appeared and ringed the crowd. Suddenly a mob started throwing stones at the police who then charged with batons and tear-gas.

Violence erupted and spread, with police stations being attacked and cars burned. By the end of the chaos 2,346 people were arrested and more than a dozen Singaporeans were killed.

The blame was squarely pinned on Lim Chin Siong who was arrested.

But did Lim Chin Siong really cause the mayhem? Who was the "mob" that started attacking the police?

At that time, Chief Minister Lim made no bones that the Lim Chin Siong was the front man for the communists who had started the violence. Lim was arrested by the Special Branch the following day.

Lim vehemently denied this accusation and countered that the chief minister was a colonial stooge. As declassified documents now reveal, Lim Chin Siong was largely right.

Entitled Extract from a note of a meeting between Secretary of State and Singapore Chief Minister, 12 December 1956, the archival note recorded that it was Chief Minister Lim who "had provoked the riots and this had enabled the detention of Lim Chin Siong."

Poulgrain even documents that full-scale military assistance was requested by prior arrangement. Singapore Governor, William Goode, acknowledged that the colonial government was not beyond employing the tactic of provoking a riot and then using the outcome to "achieve a desired political result."

Indeed, Poulgrain noted that "[Public Record Office] documents show these were the tactics of provocation that were employed in the 1956 riots that led to Lim Chin Siong's arrest."

A few weeks after Lim Chin Siong was behind bars, Lim Yew Hock visited London in December 1956 and was "warmly congratulated on the outcome by Alan Lennox-Boyd, Secretary of State for the Colonies."

And yet, in his memoirs, the Minister Mentor concludes that the Malayan Communist Party "in charge of Lim Chin Siong" were behind the whole affair and that Lim Yew Hock had purged Singapore of the communist ringleaders.

…and the talks are resurrected

And so in the 1957 with Lim Chin Siong under detention, Lim Yew Hock led the delegation to London. But during the negotiations, it was Lee who "played a crucial role in sweeping away the earlier obstacles to agreement on internal security by resurrecting the proposal for an Internal Security Council (ISC)."

The ISC was structured in a way that Britain and Malaya outweighed Singapore in the outfit. Why was the PAP supportive of such an arrangement?

Historian Simon Ball said it best: "Lee wanted an elected government but not one that could be blamed for suppressing its own citizens."

Even more damning was an archival "Top Secret" document that recorded: "Lee was confidentially said that he values the [Internal Security] Council as a potential ‘scape-goat' for unpopular measures he will wish to take against subversive activities."

But the PAP continues the charade. Recall what Dr Ow Chin Hock wrote in his letter in 1996 about the arrest of Lim Chin Siong and other Barisan leaders: "The [ISC] had a British chairman, two British members, one Malaysian members and three Singaporean members. Together these four non-Singaporeans outnumbered the three Singaporeans on the council."

In any event, unlike the one led by David Marshall, the negotiations in 1957 had little spine and gave away too much of Singaporeans' rights. As a result, both sides expeditiously reached an agreement for self-government, an agreement that Marshall called "tiga suku busok merdeka" (three-quarters rotten independence).

But self-government was not the only subject being discussed. On the side, the British also wanted to introduce a clause that would bar ex-detainees, or subversives as the authorities called them, from standing for elections.

Lee supported such a move – one that he would surely have known would cripple party comrade Lim Chin Siong's political career.

In his memoirs, however, Lee Kuan Yew wrote: "I objected to [the introduction of the clause] saying that ‘the condition is disturbing both because it is a departure from the democratic practice and because there is no guarantee that the government in power will not use this procedure to prevent not only the communist but also democratic opponents of their policy from standing for elections'."

A declassified British memo contradicts this: "Lee Kuan Yew was secretly a party with Lim Yew Hock in urging the Colonial Secretary to impose the ‘subversives ban'."

Perhaps this is not surprising as the British had noted that the "present leadership of the PAP is obsessed with the need to persuade the politically unsophisticated masses that the PAP is ‘on their side' and this involves demonstrating that the PAP is not a friend of the foreigner…"

And this is perhaps the reason why Lee told Britain's Secretary of State, Alan Lennox-Boyd: "I will have to denounce [the clause]. You will have to take responsibility."

London to the rescue…again

A few months after Lee returned from the constitutional talks in London in March 1957, the PAP conducted elections of its executive council. Lim Chin Siong was still under detention and could not challenge Lee for the party's leadership.

Lim's supporters, however, outnumbered Lee's rightwing faction and were elected to the executive council of the PAP.

The British, through Lim Yew Hock who was by then "viewed as an altogether more compliant tool of the security apparatus," ordered the arrest of Lim Chin Siong's supporters, thereby securing Lee Kuan Yew's continued control of the party.

Harper records, that despite Lee's protests against the crackdown of his party's leftwing, "not all were convinced of his innocence in the matter."

In his 1998 memoirs, Lee Kuan Yew describes the fateful detention of the PAP's leftwing leaders by giving much prominence to Lim Yew Hock's decision while adroitly playing down the role of the British.

After the talks in 1957, and given the stubbornness of Marshall and Lim in the 1956 talks, the British were persuaded that Lee was their man.

Another set of talks were arranged in May 1958 and thereafter "there was an unspoken assumption that the PAP would govern after the 1959 elections."

Writer T J S George repeated this observation that "repeated [British] intervention to ensure Lee Kuan Yew's political survival confirmed the feeling that Lee was by now Britain's chosen man for Singapore."

Poulgrain recounted his own experience with British intelligence officers who were operating in Singapore in the early 1960s. One told him about a group of officers who were listening in on Lee Kuan Yew making a speech, railing against British imperialism.

"The diatribe," Poulgrain writes, "brought only a jocular response from this group, one of whom openly commented that Lee was going a ‘bit over the top' considering that he was actually ‘working with us.'"

The historian states plainly that Lee Kuan Yew personified the essential long-term interests of the United Kingdom in Singapore.

Lee himself played up this position when he told the British government that the PAP was really London's "best ally."

The British agreed. Secret documents now show that London's assessment was that Lim Chin Siong was increasingly bringing pressure to bear on Her Majesty's Government and "unless forestalled by Lee, may well be able to make the pressure decisive."

Lee was grateful. He indicated that "he and his other reputed moderates in the PAP regard the continued presence of the British in Singapore as an assurance for themselves."

From then on, despite the British concerns of Lee's "totalitarian streak that rides roughshod over all opposition or criticism", Lee's PAP and London "became locked closer together."

Lee saw the power in Lim Chin Siong.

The failed 1956 Constitutional talks, Lancaster House, London. From right: David Marshall, then chief minister (7th), Lee Kuan Yew (2nd) and Lim Chin Siong (partially hidden). -

Part II: Get him!

9 Jul 07

After securing control of the PAP with the aid of the British, Lee Kuan Yew was still left with the problem of the detained Lim Chin Siong and his supporters.

This was a source of embarrassment for him. Seeing this, Lee announced that he would secure the release of his party comrades before taking office if the PAP won the elections in 1959.

Behind the scenes, Lee negotiated and secured the private agreement of then British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan that the prisoners would be released by promising that he (Lee) would "move against them if they departed from the party line."

In return for promising to secure their release, Lee had secured Lim Chin Siong's and other detainees' pledges of allegiance to the party's manifesto.

Following PAP's victory in the 1959 election, Lim and six other detainees, were released.

Question: If Lim Chin Siong had really been the one who started the riots in 1956, shouldn't he have been charged and imprisoned, rather then released?

In truth the PAP and the British themselves were playing fast and loose with the law. The affair confirmed suspicions that all the backroom dealings was for political ends, not national security.

In any event, Lee assigned Lim – who, if not for all the machinations, would have been the leader of the PAP and prime minister – the post of political secretary in the ministry of finance, the Siberia of politics at that time.

In the meantime, detentions without trial continued under the new Lee government and the ISC continued to be used as a front for the PAP's acts.

An indecent proposal

Fed-up with Lee's autocratic style and the delay of releasing the remaining detainees, PAP MP and mayor Ong Eng Guan denounced the government for its dictatorial methods and moved a motion in the Legislative Assembly to abolish the ISC.

Harper wrote that because of the secrecy under which the ISC operated "not all members of Lee's cabinet were aware that the Singapore government had not pressed for the releases since early 1960."

In his memoirs, Lee wrote that "Lim Chin Siong wanted to eliminate the Internal Security Council because he knew that…if it ordered the arrest and detention of the communist leaders, the Singapore government could not be held responsible and be stigmatized a colonial stooge."

What the Minister Mentor did not say, but what Harper reveals in his chapter, is shockingly contradictory: "In mid-1961, therefore, to seek a way out, Lee suggested to the British that his government should order the release of all [the remaining] detainees, but then have that order countermanded in the ISC by Britain and Malaya."

Such a craven act was even rebuffed by the British. The acting Commissioner, Philip Moore, stated that the British should not be "party to a device for deliberate misrepresentation of responsibility for continuing detentions in order to help the PAP government remain in power." (emphasis added)

Moore suggested that the best solution would be "to release all the detainees forthwith." Lee, however, "was unwilling to present the left with such a victory."

In a most damning indictment, Moore said that Lee "has lived a lie about the detainees for too long, giving the Party the impression that he was pressing for their release while, in fact, agreeing in the ISC that they should remain in detention."

And if one thought that Lee Kuan Yew could not sink any lower, he did. He turned to his saviours and warned that should he lose in an upcoming by-election, he would call for a general election, which he fully expected to lose.

This was because he was facing defections in the Legislative Assembly on his refusal to release the remaining detainees. And should he lose the elections, he warned the colonial masters, David Marshall, Ong Eng Guan and Lim Chin Siong would form the next government.

This, he calculated, would be so distasteful to the British that it would rally them to his side.

He presented the scheme at a dinner with Commissioner Lord Selkirk, Philip Moore (Selkirk's deputy), and Goh Keng Swee: Lee would order the release of the prisoners, the British would stop it through the ISC, and he would then announce a referendum on merger with Malaya (the story behind merger is explained below).

This would provoke opposition from his party mates as well as Lim's supporters whom he would then banish to Malaya.

A 1961 memo between the then Commission in Singapore and the Colonial Office in London revealed that Lee calculated that this move "would force Lim Chin Siong to reveal his hand completely and resort to direct action, in which event the Singapore Government would relinquish power and allow the British or the Federation to take over Singapore."

In short, Lee was willing to sacrifice the efforts to secure the independence of Singapore to achieve his own political ends!As it turned out, Selkirk wanted to have nothing to do with the "unsavoury" proposal.

Merger – on one condition

At about this time, Malaya's Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman revived the idea of a federation of Malaysia consisting of the Borneo territories (now Sarawak, Sabah, and Brunei), Malaya (now peninsular Malaysia), and Singapore.

In exchange for territorial concessions in Borneo, the Tunku as the head of the federation would allow Britain to maintain a strategic presence in Singapore.

The proposal was put forward because the Tunku was having problems of his own with the left in Malaya. This was not helped by the strength of Lim Chin Siong's left in Singapore. Kuala Lumpur saw the necessity of crippling Lim's support and wanted Lee to be its hit-man.

For the British, the idea of a Malaysian federation was an acceptable compromise because it allowed London to maintain influence in the region while relinquishing its colony which it was going to lose anyway given the irresistible anti-colonial sentiment fanning the globe at that time.

As for Lee Kuan Yew, the idea was heaven sent. Harper documents that Lee saw the Tunku's concept of a "Malaysia" as crucial to his own political survival because of the growing strength of the left.

The left's strength was amply demonstrated when Lee's rightwing faction lost two by-elections in quick succession – the first to Ong Eng Guan in April 1961 (Hong Lim) and the second three months later to David Marshall (Anson).

Lee was rattled. Then PAP chairman, Toh Chin Chye, recalled: "He was quite shocked. He drew me aside after the results were announced and asked me what to do. I said, 'Hang on!'"

Toh also revealed that Lee had written to him that "the trade unions, the Middle Road crowd wanted him to resign" and that they wanted him to replace Lee as the prime minister.

Toh did not recommend Lee's resignation. But the reason he gave was that it "would divide the government and it would appear to the people of Singapore that we were being unsteady," hardly a ringing endorsement of Lee's leadership.

These developments precipitated an open split between Lee and Lim Chin Siong. Lim's group suspected – correctly – that Lee was up to no good in his pursuit of merger with Malaysia and they openly called for the abolition of the ISC.

In July 1961, legislative assemblymen, parliamentary/organising secretaries, and members of the PAP split from the party and formed the Barisan Sosialis. Lee's party was shaved to bare bones.

At the time, Harper writes, "there was an immense political momentum, a sense that the future lay with the Barisan Sosialis."

Even then, Lim Chin Siong never wavered in his commitment to governing Singapore in a democratic way when he wrote in a press statement that "any constitutional arrangement must not mean a setback for the people in terms of freedom and democracy."

This contrasts with the PAP's demonisation of Lim as a front for the communist out to destroy the democratic way.

Closing in on Lim

Meanwhile In Malaya the Tunku insisted that Lee re-arrest Lim Chin Siong before he would allow Singapore into the federation.

One of the reasons was because if the detention was conducted after merger, the Kuala Lumpur government would be responsible for it and it would be seen as cracking down on the Chinese in Singapore, increasing communal tensions.

As for Lee's part, he saw the detention of Lim as his trump card and wanted to secure the merger first before he moved against the Barisan leader; Abdul Rahman would have no incentive to proceed with merger once the threat of Lim was removed.

But the Tunku was firm: No detention of Lim, no merger. Lee knew he had to act.

And so a two-part plan was hatched to bait Lim and colleagues: "In the first phase, the Barisan would be harassed by the police and the government. This was designed to provoke it into unconstitutional action, which would initiate a second phase of detentions, restrictions and other actions to be sanctioned by the ISC."

Lim's opposition of allowing the British to retain powers of detention during the constitutional talks in 1956 rang truer than ever and Marshall's colourful description of "Christmas pudding and arsenic sauce" were beginning to sound very apt.

The diabolical scheme was vehemently opposed by the British Commission in Singapore. Lord Selkirk told his superiors in London that "in fact I believe that both of them (Abdul Rahman and Lee Kuan Yew) wish to arrest the effective political opposition and blame us for doing so."

In the months leading up to Lim's arrest, Selkirk wrote to his superiors in London again, imploring them not to cooperate with Lee:

"Lee is probably very much attracted to the idea of destroying his political opponents. It should be remembered that there is behind all this a very personal aspect…he claims he wishes to put back in detention the very people who were released at his insistence – people who are intimate acquaintances, who have served in his government, and with whom there is a strong sense of political rivalry which transcends ideological differences."

Contrast this to what Lee wrote in his memoirs in 1998: "Lim Chin Siong…knew that if he went beyond certain limits, [the ISC] would act…"

Lim need not have gone "beyond certain limits" as declassified documents now reveal, Lee was determined to put him in prison, communist or not, limits or no.

More shamefully, Lee will not admit that he was the one who had pushed for Lim's detention.

Selkirk's deputy, Philip Moore, reviewed intelligence reports and concluded that there were no security reasons to detain Lim Chin Siong: "Lim is working very much on his own and that his primary objective is not the Communist millennium but to obtain control of the constitutional government of Singapore."

But London was determined not to allow democratic scruples from getting in the way of its strategic presence in Southeast Asia. It acquiesced to Lee's plan.Lim Chin Siong garlanded upon his release on 4 Jun 1959.

"Lee is probably very much attracted to the idea of destroying his political opponents. It should be remembered that there is behind all this a very personal aspect…he claims he wishes to put back in detention the very people who were released at his insistence – people who are intimate acquaintances, who have served in his government, and with whom there is a strong sense of political rivalry which transcends ideological differences."

- Lord Selkirk,

British Commissioner to Singapore -

Part III: The end of Lim Chin Siong

9 Jul 07

In February 1963 the ISC, under the direction of Lee, ordered Operation Coldstore where 113 opposition leaders, trade unionists, journalists, and student leaders who supported the left were arrested. Top of the list was, of course, Lim Chin Siong.

Historian Matthew Jones recorded that the arrests "primarily reflected the imperative felt by the decision-makers in London to respond to the needs and demands of the nationalist elites."

Not for the first time, the British had come to the rescue of Lee Kuan Yew.

Behind bars, torture and psychological abuse were meted out in liberal doses. Amnesty International documented much of this in a report in 1981.

The state of Lim Chin Siong under detention makes for sordid reading. According to (the late) Dennis Bloodworth, Lim came close to taking his own life while in detention. He had gone into depression. In 1965, when he was at the Singapore General Hospital Lim tried to hang himself from a pipe in the toilet. He was rescued just in time. After he recovered he was sent back to prison.

Four years later, he penned a letter to his former comrade-turned-arch-enemy and capitulated, saying that he had "finally come to the conclusion to give up politics for good" and repudiated the "international communist movement."

Even then, Lee banished Lim to London in 1969 and allowed him to return to Singapore only ten years later.

What kind of treatment Lim received at the hands of his foes that turned him from a spirited and charismatic national leader who walked tall among his people into a forlorn political non-entity, Singaporeans can only imagine.

For Lim is not talking, he passed away in February 1996, forever carrying his secrets with him to his grave.

It was not Britain's finest hour. Far from the honest-broker that everyone had expected Britain to be, the UK Government had actively engineered Lim's downfall and Lee Kuan Yew's capture of the prime ministership.

As it is, the historic account is hardly a heroic tale of the PAP's courageous triumph over the Barisan, as official accounts would have us believe.

Instead, declassified documents now show that it was a sad tale of private dealings and cowardly machinations for the attainment of power.

At his funeral which overflowed with his former Barisan comrades and supporters, eulogies recounting Lim's selfless dedication to a free and democratic Singapore were read. As his casket was pushed into the furnace, a thunderous and defiant applause resounded.

Referendum: To merger or to merge?

After having fulfilled his promise to Tunku Abdul Rahman to arrest Lim Chin Siong before merger, Lee set his sights on taking Singapore into Malaysia. He called for a referendum to obtain the people's mandate for the move, a decision that Britain and the Tunku objected to.

A referendum was hardly necessary as Lim and other Barisan leaders were behind bars. One suspects that a vote was needed to give the PAP the mandate to move in this direction.

Indeed Lee, with not little false bravado, wrote in his memoirs: "I remained determined that there should be referendum."

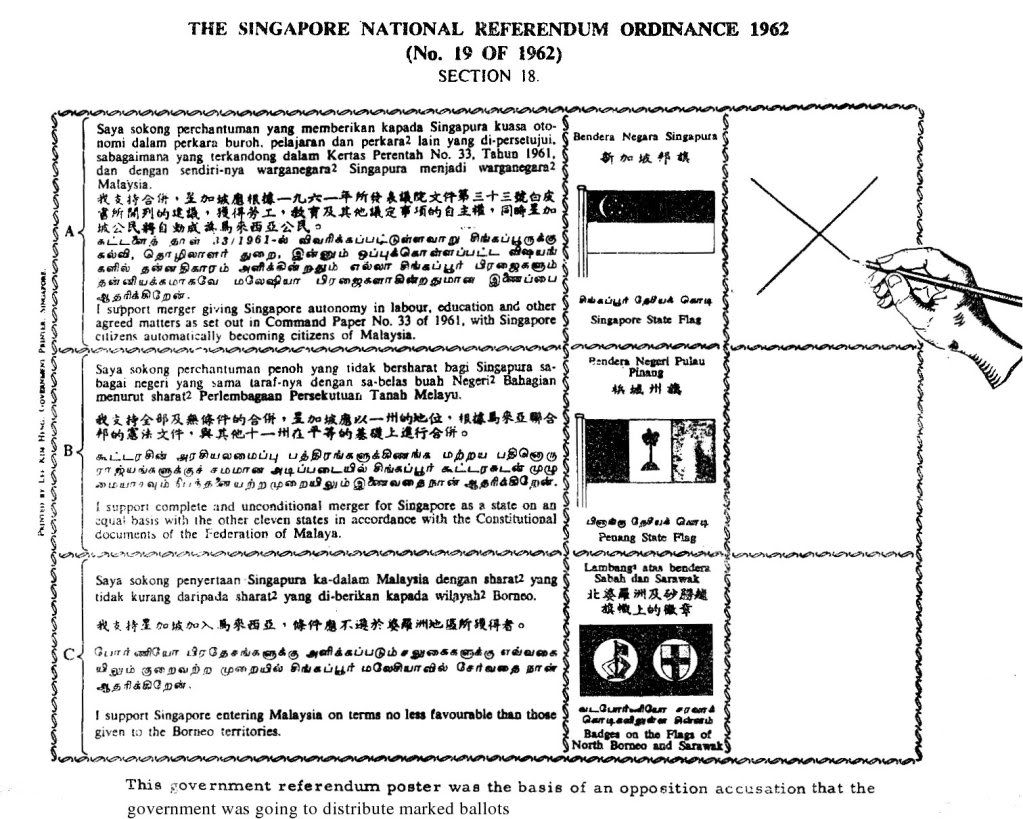

Democratic? Hardly. Instead of asking Singaporeans to vote for ‘yes' or ‘no' to merger, Lee proposed a ballot that allowed the people to vote only for merger under three options:

Do you want merger?

A. in accordance with the white paper, or

B. on the basis of Singapore as a constituent state of the Federation of Malaya, or

C. on terms no less favourable than those given to the three Borneo territories?

And so after the referendum in September 1962, Singapore moved one step closer to becoming a part of an independent Malaysia.

Regrettable but necessary?

Lee Kuan Yew, would have us believe as he wrote in his memoirs, that the use of detention without trial was "most regrettable but, from my personal knowledge of the communists, absolutely necessary."

Harper dismisses this argument: "It was…inadmissible to argue, as Lee Kuan Yew did, that the exercise of these powers was ‘regrettable', but dictated by historical necessity."

The truth is that "through this adversity…the Barisan Sosialis still adhered to constitutional tactics."

Indeed, in the entire campaign to cripple the opposition, Lee Kuan Yew and his rightwing PAP faction has repeatedly resorted to using desperate measures of detention without trial, brazenly accusing his opponents of being a front for the communists.

Harper makes it even more explicit:

"After 1959, Lee Kuan Yew had urged the necessity of defeating the radical left through open democratic argument, whilst trying to provoke them into extra-legal action. The left, however, had not been deflected from constitutional struggle. Therefore, from mid-1962 at least, Lee concluded that this confrontation could only be resolved by resort to special powers that lay beyond the democratic process. This merely exposed the extent to which the crisis, as the British argued, a political one, and not a security one."

The last chapter

Lim Chin Siong's fight for Singapore may have come to a close, but another one is just beginning – the fight for history to be written the way it should be.

Declassified secret papers are beginning to provide a glimpse into what really took place during the 1950s and 60s, especially in the behind-the-scenes dealings.

Beginning with Comet In Our Sky more will be revealed. But as Harper tells us "many files remain closed and many files that have been released have had key documents ‘retained' by the original government department." These include key documents on Lim Chin Siong's detention in Operation Coldstore in 1963.

As the real story emerges, the Singapore Democrats will play our part to urge this process along – in cyberspace – thus ensuring that the memory of Lim Chin Siong and what he and his Barisan colleagues did for Singapore will forever remain with us.

This is crucial as our past is still our present. Lim had argued that arbitrary powers of detention without trial, in whoever's hands be they white or yellow, will continue to make Singapore unfree and our struggle for independence elusive.

"The people ask for fundamental democratic rights," he argued, "but what have they got? They have only got freedom of firecrackers after seven o'clock in the evening. The people ask for bread and they have been given stones instead."

More than half a century later, can any Singaporeans say with hand on heart that Lim Chin Siong was not right? -

Lim Chin Siong, right, selling fruits in Bayswater, London, 1970s.

Lim Chin Siong in Desaru, Malaysia, in 1995, a few months before he passed away.

-

Part IV (final): What they teach in school

In case you're wondering what they're teaching our kids in school about Mr Lee Kuan Yew and the PAP, take a look at this.

One textbook for GCE O-level students and approved by the Ministry of Education started off thus:

"There was always a significant Chinese-educated faction within the party that held a different political view. From its founding, this faction was led by Lim Chin Siong, who adopted violent strategies through riots and street demonstrations. As this division developed, it split the party into two wings: the non-communist wing led by Lee Kuan Yew and the communist wing led by Lim Chin Siong."

Describing Lee as someone who "championed the causes of ordinary people and gained their trust and respect," the book goes on to enumerate some of Lee Kuan Yew's political activities that brought him to prominence.

One such activity was Lee's cooperation with the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) who wanted to work with the PAP "because Lee Kuan Yew was reliable and his name inspired confidence."

The textbook also teaches that the constitutional talks in 1955 happened because as "major leaders such as David Marshall and Lee Kuan Yew both demand[ed] self-government (and merger with the Federation of Malaysia), the British were forced to increase the speed of reforms."

But the British, apparently, found David Marshall to be a "weak and indecisive

leader" and were thus "reluctant to grant self-government to such a leader." This, the text says, was the reason why the London talks in 1955 were unsuccessful.

Then there was the crackdown on the PAP's leftwing in 1957 after Lim Chin Siong's faction won the leadership of the PAP. The book left us with no doubt that "The communist success in this party election…was achieved with some deception."

As a result Lee Kuan Yew and five of his closest supporters resigned from the executive offices of the PAP "in disgust" which meant that "the PAP, a legal party, was now captured by the illegal communists."

The text adds that this was "the classic strategy that the communists called the ‘united front'" and that "this incident explained why the PAP leadership regarded election as serious business even till today."

Following the resignation of David Marshall, negotiations with the British to grant self-government went much smoother because, with Lim Yew Hock as Chief Minister, prospects of reaching an agreement on how to "deal with the threats posed by the communists" were much better.

There was no mention of Operation Coldstore.

And the correct answer is…

Another book, a self-study revision programme for Secondary 2 students "based on the New Syllabus by Ministry of Education", compiled a series of study notes and questions. Correct answers were provided at the back of the book.

Some of the multiple-choice questions went like this:

I. The ______________ in the PAP supported the Communists.

(1) radicals

(2) liberals

(3) proposers

(4) proponents.

Answer: (1) radicals

II. Which statement about the man in the picture is incorrect? [Picture of LKY]

(1) He was the one who wrote the Singapore's national Pledge.

(2) He was Prime Minister of Singapore from 1959-1990.

(3) He changed Singapore from a third world country into a first world state.

(4) In 1956, he stood as a PAP candidate in Tanjong Pagar Constituency.

Answer: (1) He was the one who wrote the Singapore's national Pledge.

III. The party symbol of the PAP is __________.

Answer: (c)

IV. The PAP had a _________ plan for Singapore and it was an honest party.

Answer: comprehensive

What is your opinion about Lee Kuan Yew?

Students were also asked to read extracts and then answer questions.

Extract A:

"And we needed somebody like Lee Kuan Yew, who can be strong and firm when needed to be, to get things done. I think Singapore was fortunate to have men like Kuan Yew and Goh Keng Swee at the helm in 1965 to do what was needed. It was Lee Kuan yew's' [sic] characteristic [sic] – when you accept to do a job, do it well – or else don't' [sic] accept the position if you are incapable of doing it."

Question 1:

In your opinion, to what extent is the above write up true of Lee Kuan Yew correct (sic)? (5 marks)

Answer:

I feel the above extract is very true. He was Singapore's first Prime Minister. He held that post from 1959-1990. He is widely acclaimed by Singaporeans and people world over as the architect of Singapore. He is responsible for transforming Singapore into a modern city. He made Singapore stable and secure. He saw Singapore through the years of merger and separation. He fully understood the challenges a small independent nation would face. Singapore had no natural resources. Singapore had limited land. The only asset Singapore had was its people.

To make an island with any constraints prosper must have been a challenge to him. His philosophy was if you take on the job, you have to do it well without any excuses or "ifs" and "but". If you feel you cannot handle a particular job, then don't take it.

The Singapore after the Japanese occupation, the Singapore after its separation from Malaysia was one full of problems, full of challenges. He, as Prime Minister, at the helm of the government, was worried but not negative in his thinking. He knew Singapore had to survive as an independent nation and he was determined to make Singapore succeed.

It is true that we needed someone of Lee Kuan Yew's calibre to steer Singapore at that time. It is also true that Singapore and the people of Singapore were fortunate to have him at the head. What we are enjoying today, all the comforts, high standards of public health, education, housing, transport and communications are all the results of the dedicated, untiring, unselfish work of Lee Kuan Yew and his team of leaders.

Question 2:

Enumerate some of the qualities of Lee Kuan Yew that you can infer from the passage. (3 marks)

Answer:

Strong character. Firm when one has to be firm. A man with a vision. An optimist. An untiring worker. Determined and dedicated. One who is not daunted by problems or challenges. One who executes whatever job he takes well (sic). One who sets a goal and works towards that goal.

Extract B:

"Indeed, the traits by which Singaporeans are known today are the very same ones that characterize Mr Lee Kuan Yew. Like the man, the country and its people are known for being pragmatic, law-abiding, hard-working and fond of a clean, clinical environment be it in business rules or physical landscape."

Question 1:

What traits of Mr Lee are mentioned in this extract?

Answer: He is pragmatic, law-abiding, hard-working, corruption-free (clean). He is a man of integrity.

Question 2:

What is your opinion of the above extract?

Answer:

The extract gives a very true picture of Mr. Lee. His government is a clean one. The hand of the law come hard (sic) on those who commit offences or resort to corrupt practices. His hard work is evident in all sectors. We are enjoying a trouble free life because of his hard work. Singapore is clean and green city (sic). The honest leaders have succeeded in attracting foreign investors to invest their money in Singapore. What is more than all these is:- The leaders have set a good example and have passed on all their good qualities to the people of Singapore. Most Singaporeans are hard working, law abiding and honest in their dealings - be it business or personal commitments. I fully agree that all the peace, stability and security that the people of Singapore are enjoying today are the result of our hard working, honest and sincere Prime Minister and his team. -

-

so the Brits (jew-controlled) help their puppet LKY to power........

the winner re-write history.............

-

Originally posted by Rock^Star:

Wah, It really brings back my secondary school memories.

-

Interesting read. Read from head to tail... Thanks for posting.

-

Actually LKY's authoritarian streak could already be seen way back in 1962. He probably saw most singaporeans as a bunch of uneducated citizenry who didn't know what's good for them. It happens even till this day:

In 1962, a Referendum was conducted to see what Singaporeans think about the prospects of merger with Malaya. The people were given 3 options :

Option 1 : Merger with autonomy in Labour and Education matters

Option 2 : Unconditional merger making Singapore on par with any Malayan state.

Option 3 : Merger under terms not worse than the Borneo states.

There was no Option available if you do not wish for merger with Malaya.

-

Just a few years back in the 50s, he was talking about freedom of speech and expression in parliament. I think when LKY really goes six feet under, real history would portray him as a brilliant and decisive leader yet one who is prepared to slither his away around in order to let the ends justify his means.

Think bukit ho swee fire (current area near tiong bahru plaza). There's still a rumour till this day that he instigated it so that the slums may be removed and his proposed flats may take place. Of course, this is just a rumour but never say never.

-

End of the day, politicians are simply liars out to win your vote. Vote the one who does the least damage into parliament.

-

WOT.

-

What's WOT? lol

Anyway, when suharto was president of indonesia, the school textbooks were full of praise for his government. And there was no internet back then. When other presidents like habibie and megawati took over, indonesians began to realise they have been fed bullshit all these years.

The same thing will happen to LKY. He has done a lot of good for singapore....no doubt. He will be remembered as one of the great men of the nation but historians will also write about him in ways he would never have consented to if he were still alive.

Wow, on that aspect alone, from where do we start? That list shall be endless. Let's start with the Lee & Lee's monopoly on HDB conveyancing fees all these freaking years :)

-

LKY says the reason why we don't have Fortune 500 companies is because we are too small a population.

Saturday, January 22, 2011

Why S'pore can't produce a Fortune 500 company

SINGAPORE is too small and its talent pool is too small to produce a world-class manufacturing giant of the Fortune 500 class.

It must therefore continue to rely on foreign multinationals to drive its growth, despite best efforts to nurture local enterprises.

Minister Mentor Lee Kuan Yew expressed this view when he was interviewed for the book, Hard Truths, launched yesterday.

Asked by a team of Straits Times journalists about the direction for the Singapore economy, he was blunt about the impact of the country's small size and limited talent pool on companies' ability to grow, especially in manufacturing.

'Look, unless you are big enough, the champions in any particular industry will be the ones who are the best in their field,' he said.

He cited Hong Kong, with seven million people. 'What has Hong Kong got? Property developers and market players. Is Li Ka Shing making a product that is selling worldwide? No, he's just acquiring real estate, ports, retail stores and telecoms companies.

'What is the most successful company in Hong Kong? (Trading company) Li and Fung. Two bright brothers, but they are in logistics chains for every company. They're not in manufacturing because they can't compete.'

Even Taiwan, with 20 million people, has fallen on hard times, for all its electronics manufacturing successes.

In Singapore, digital entertainment products maker Creative Technology, once Singapore's tech golden boy, has found the going tough.

'Creative was one of the few companies that were trailblazers. But look at the trials and tribulations they had to go through. They've had to recruit people from Silicon Valley to keep up with the competition because Singapore doesn't have the critical mass of talent,' he said.

And even if a company grows and is successful, it will eventually be gobbled up by bigger companies. 'Get to world class and there will be a company that's eyeing all these possible take- overs,' he said.

He cited food manufacturer Tee Yih Jia, founded by 'Popiah King' Sam Goi, which sells its frozen food products overseas including in the United States.'Once it begins to succeed in America, it will be taken over by conglomerates like PepsiCo,' he said. 'How do I know? Because I've attended PepsiCo meetings. They collect foodstuffs from around the world and sell them in their outlets in Latin America and in all the cinemas across the world.

'They will buy up Tee Yih Jia, and Tee Yih Jia can't compete with them because where are its outlets?'

Mr Lawrence Leow, president of the Association of Small and Medium Enterprises, agreed that Singapore faced insurmountable challenges to producing a global manufacturing company.

But he felt Singapore could produce global companies in other areas. For example, technology companies like Facebook need not be constrained by the country's size. Singapore could also attract foreign SMEs to team up with local ones, he added.

Mr Douglas Foo, founder and chief executive of Sakae Holdings, which has 40 sushi restaurants in Singapore and 30 more overseas, said Mr Lee's comments reflected the 'real and brutal facts of the business world'.

Adapted from an article on the ST, 21 Jan 2011 -

LKY caught selling rojak.

-

Is it strange to anyone that Singapore does not have a fortune 500 company in the year 2010? Well, at least no company that originated from Singaporeans.