Let’s not forget our multilingual roots

-

Let’s not forget our multilingual roots

Thursday, 10 December 2009, 9:35 am | 42 views

Jamie Li Chou Han

In the recent public debates over the future direction of Singapore’s Chinese language education policy, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong is right in noting that much of the discussion has revolved around emotional responses regarding what level the language should be pitched at (‘Help every child go as far as possible’, The Straits Times, 4 Dec 2009).Such emotive reactions are to be expected when it comes to discussions on language issues in general, as shown by the recent furore over the English language standards of Singaporeans. This is because language is perceived by many to be, rightly or wrongly, a cornerstone of one’s cultural and ethnic identity. German philosopher Martin Heidegger even goes so far as to proclaim that the essence of our being is to be found in language.

PM Lee has justifiably sought to depoliticize the Chinese language issue by calling for a rational approach towards what he sees as mainly a pedagogical issue. However, what he failed to address, and which is largely missing in the public discourse on the teaching of the Chinese language – and Mother Tongue policy in general – is precisely the inherent political nature of the issue.

This blind spot has resulted in the lack of serious public discussions on the long-term implications of the State’s current language policy for the fabric of our society as well as its effects on Singapore’s image on the larger geopolitical stage.

At the domestic level, the state’s preoccupation with propagating the Chinese language at the expense of the other official languages has the unfortunately political effect of giving minorities the impression, true or otherwise, that the State, rather than being a secular and impartial entity, is actually bias towards the dominant ethnic group.

While policymakers have tried to justify the disproportionate allocation of public resources towards cultivating a bicultural elite fluent in English and Chinese on pragmatic grounds, specifically their usefulness in international trade, scant attention has been paid towards the tensions that such a policy can and has created in our multicultural, cosmopolitan society.

What is being advocated here is not a rigid attitude of political-correctness towards minorities, or worse still a token effort at portraying impartiality through positive discrimination, but rather a serious reconsideration of the potential pitfalls of linking language to ethnic/racial identity and then actively promoting certain languages over others in the name of pragmatic economic concerns. Pursuing such a policy will lead to more Singaporeans asking: Are we truly one united people, regardless of race, language or religion?

The impact of the current language policy extends far beyond the domestic realm, affecting the image that Singapore projects on the wider global stage. Since our independence, much effort has been made at the diplomatic level to cultivate the image of Singapore as a non-aligned, secular country that seeks to make as many friends as possible on the international stage rather than stick to strictly defined ideological, cultural or civilizational blocks. Such a policy is even more important in today’s geopolitical climate, which some are keen to portray as a clash of civilizations.

Language has played a key role in portraying Singapore’s cosmopolitan image overseas, with our pioneering political leaders choosing to adopt Malay as the national language and English as the language of governance, while giving minorities the secular space to maintain their own languages. Such measures were and are still needed if we are to continue persuading our neighbours and the international community that we are a secular, multicultural nation that does not intend to cultivate a special relationship with one particular country mainly due to perceived cultural and ethnic ties.

In the struggle for independence, our founding fathers played a risky political game of riding the communist tiger and succeeded, albeit by the skin of their teeth. The question for us today is if we should tempt fate once more by riding a much more unpredictable rising dragon. Unfortunately, the answer cannot be found through the use of language teaching tools boosted by technology – a troubling thought indeed for those who see language as merely a pedagogical issue.

-

Should the use of dialects be encouraged once more?

Tuesday, 30 June 2009, 10:31 am | 2,569 views

Cerelia Lim

Should the use of dialects be encouraged once more?

Should the use of dialects be encouraged once more?This question was the focus of the Dialect Forum: The Forgotten Tongue hosted by the People’s Youth Association Movement at Toa Payoh Central Community Club on 27th June.

“I will say that dialects made my life colorful, but beyond that, in the area of work in the professional life, it was mandarin that made the difference,” summed up Mrs Josephine Teo, MP for Bishan- Toa Payoh GRC.

Mrs Teo, who speaks Hakka, Cantonese and Hokkien, is also the GPC chairman for education. She was present as one of the panelists at the forum.

Having studied in Dunman High, a Special Assistance Plan (SAP) school, Mrs Teo had a good grounding in mandarin. This stood her in good stead when she accepted a posting to work on the Suzhou Industrial Park Project. Although she spoke Hakka at home, she mastered English and mandarin at school. Cantonese was learnt from accompanying her grandmother to the market. And, as her family owed a shoe shop in Geylang, she learnt how to speak Hokkien and a smattering of Malay.

In the early days of Singapore, the majority of the Chinese community spoke their native dialects. Mandarin was rarely used and English only utilized for official businesses as we were a British colony then.

In the early days of Singapore, the majority of the Chinese community spoke their native dialects. Mandarin was rarely used and English only utilized for official businesses as we were a British colony then.In 1979, in a bid to simplify the language environment and improve communication amongst the different dialect groups within the Chinese community, the Speak Mandarin Campaign was launched by then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew.

The present Chinese community of today is mostly bilingual in English and mandarin. Amongst the Generation X and Y, dialects are a tongue unknown to them, a language of their grandparents’ era.

However, has the gradual phasing out of our dialects erased more than just a local lingo?

Mr Danny Yeo (Yang Jun Wei), a panelist and also a Chinese studies lecturer with Ngee Ann Polytechnic, told participants that in many of his drama performances at Chinatown, he often finds himself using dialects, instead of mandarin to engage the audience. He mentioned that his ability to speak Cantonese opened up doors and unlocked the obstacles between the audience and himself.

Medical doctor, Mr Yong Tong, who is also the chairman of the Chinese association (Youth Wing), recounted that learning English and Chinese at the first language level allowed him to do his Executive MBA in Chinese but it was dialect that allowed him to communicate with his patients in the hospitals.

Another participant of the forum, Ms Xuan Na, a Human Resources practitioner who studied in Special Assistance Plan (SAP) schools, questioned if our pursuit of the bilingualism policy is at the expense of dialects.

Another participant of the forum, Ms Xuan Na, a Human Resources practitioner who studied in Special Assistance Plan (SAP) schools, questioned if our pursuit of the bilingualism policy is at the expense of dialects.In defense of the policy, Mrs Teo replied that as a parent if her children are able to master English and mandarin well, she would have no problems if they wanted to learn dialects as well. However, she reiterated that we should not have the belief that being able to speak a variety of languages is better than being able to speak well in a lesser number of languages.

“Must it be assumed from the Speak Mandarin Campaign and the educational policies that the advocation of dialects come at the expense of English and mandarin?” Sherman, a Nanyang Technological University undergraduate.

Elaborating further, he said that dialects have a role in society and their role is in our cultural identity. He also asked if there was a need to believe that learning of dialects will compromise learning standards of other languages and proposed that we appreciate our rich linguistics mix.

In response, Mr Yeo said that he is an advocate of promoting mandarin and protecting dialects. He feels that we need to look at the language abilities of the youths today and compare it to the youths 10, 20 years ago. He said that if the language capabilities of the youths have decreased over the years, then a review of the language policy should be conducted.

However, he also added that besides education, there are other ways of learning dialects such as watching popular Hongkong Cantonese dramas on cable.

Ms Jillian Tiong, a Fuzhou native who has lived in Singapore from more than 20 years, concurs and said that learning dialects is not a difficult thing.

“I learnt my dialects from speaking with children. If you really want to learn, it is not impossible.”

-

Beyond dialects and languages

Friday, 27 March 2009, 11:19 am | 1,224 views

Kelvin Teo / TOCI Writer

So the dust has now settled over Minister Mentor Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s provocative call to chinese Singaporeans to focus on learning mandarin instead of their dialects. From a personal perspective, I didn’t find Mr Lee’s call surprising, given the fact that he has always championed Singapore’s role as the gateway to China. There have been exhaustive discussions on the domestic cultural impact of Mr Lee’s remark but little attention is paid to the political economy beyond the dialects and languages.

Geopolitical shift towards East Asia

As the fallout from the current global credit crisis continues, there has been some talk of America losing its superpower status as it reels from a double whammy – the collapse of its financial system and the overstretching of its military in Iraq and Afghanistan. And naysayers have further rubbed salt into the wound by predicting that the US dollar will lose its world currency status. The writing is already on the wall when OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) countries started dumping the dollars. Iran transacts in Euros with Venezuela following suit. And after the dollars hit its lowest against the yen, the likelihood of the former being knocked off its pedestal seems closer to reality.

There could be a shift in the balance of world power, a transition from one dominant entity to a few powerful entities. The BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) nations seem the likely candidates. China is poised to overtake America in terms of GDP by 2040. For ASEAN nations, trading volume with China is set to rise with the establishment of the ASEAN-China Free Trade Area by 2010. The value of ASEAN-China trade was forecasted to hit $200 billion in 2008.

The Kra Canal Project, which is the planned waterway link between the Indian ocean and the South China sea and cutting across the Isthmus of Kra is in its revival stage. The Chinese will be providing assistance for the project, and it is a move to increase Chinese commercial and military presence within Southeast Asia, particularly in facilitating trade and enhance Chinese energy security. So the geopolitics shift and anticipation of increased trade links with China within the region might make learning mandarin an attractive postposition, no? Perhaps, there is use for learning mandarin after all. However, wouldn’t it seem a little premature to place the learning of our dialects into the backburner?

Mandarin alone offers no comparative advantage

Cantonese speakers amongst us might have a strong case for argument here. Cantonese makes up 15% of the Singaporean chinese population. Cantonese is spoken as a medium of communication in Guangzhou, a major business centre in China. And it will come in useful when interacting with business people from Hong Kong too. However, it is a fallacy to think that being chinese and able to speak mandarin would eventually lead to a comparative advantage. The failure of the Suzhou Industrial Park (SIP) serves as an important reminder to all of us.

SIP was initially conceived to the epitome of Singapore-style Industrial Township – a showcase of Singapore’s way of managing an industrial set-up. That wasn’t to be, and Singapore transferred a major part of SIP’s ownership back to the Chinese. What happened was that SIP was outgunned and outfoxed by the Suzhou New District, despite the former enjoying advantages ranging from initial political support from the Chinese Communist Party to freedom over planning and land use. The experiment to clone Singapore in China failed. Thus, what the SIP failure has taught us is that common language is no substitute for the appreciation of local political, social and economic culture. While learning the language or dialect involved in trade communications is important, but the key to survival is to be able to adapt to the prevailing business conditions.

Keeping Singaporeans at home

Last but not least, the very notion of home is increasingly diluted in Singapore. The Asia Research Centre of Murdoch University reported in December 2007 that 53% of Singaporean teens would consider emigration to greener pastures. Singapore’s outflow of 26.11 emigrants per 1000 citizens is ranked 2nd highest in the world, after Timor Leste. Deputy Prime Minister Wong Kan Seng also publicly acknowledged that Singaporean applications for overseas residency have already exceeded 1000 per month since 2007.

While many have attributed the emigration trend to better economic opportunities abroad, there are other push factors in Singapore that contributed to it. The growing disconnect between Singaporeans and their social environment, the OB markers keeping Singaporeans from taking ownership of their own identity in Singapore are among the push factors. Dialects play an important role in not only building a strong sense of identity towards one’s community, but also encourage Singaporeans to take pride of our own cultural diversity. If we cannot be proud of our own cultures, why would we even hold allegiance to this country by staking our individual economic futures here?

——–

About the writer: Kelvin Teo works in the healthcare sector. He also writes for the independent NUS daily The Kentridge Common.

-

Disadvantageous Mandarin

Thursday, 19 March 2009, 6:23 pm | 4,009 views

A response to MM Lee

KJ

There is a lot to be said for Singaporean-Chinese, myself included, to be ascribed a ‘mother tongue’ that is not really my mother’s (or for that matter, my father’s), one that we have to learn from scratch, in effect as a second-language, and one with which we have little affinity.

There is a lot to be said for Singaporean-Chinese, myself included, to be ascribed a ‘mother tongue’ that is not really my mother’s (or for that matter, my father’s), one that we have to learn from scratch, in effect as a second-language, and one with which we have little affinity.What is more lamentable is the fact that these decisions are borne out of unquestioned, state-mandated economic necessity, and subsequently implemented with such swift ruthlessness. Cold, hard-headed decisions that, without our realizing, put a stopper to our personal relations and halt our life stories. How many times have I found great difficulty in conversing with my grandparents, who were by then too old to abandon their original tongues and acquire new ones, while I on the other hand had been discouraged from speaking in their native ones (i.e. my real mother tongue[s]), and force-fed a foreign language called Mandarin.

Singapore prides itself on arriving from ‘Third World to First’ in one generation – (have we really?) – this is the same reason for our extraordinary ability to extinguish our rich southern Chinese heritage, one that is as old as centuries if not the millennia, in a single generation.

Is this something that we, that is to say, Singaporean-Chinese, in the name of economic achievement should be proud of?

I doubt that our ability to speak Mandarin has been, as MM Lee would have us believe, a ‘key advantage’. As academic Linda Lim remarked in an interview with the Straits Times last week, our self-appointed role as conduits to China and India is counter-productive, if not redundant. And after expending so much energies and resources into its teaching and learning, how many of us are truly proficient in Mandarin, beyond the rudimentary phrases needed to get one past the wet market?

Having to master both English and Mandarin without a ‘natural’ cultural-linguistic environment that is necessary for one to be proficient in either language has resulted in us floundering in both. Drowned in this process is our chance and ability to master our true ‘mother-tongues’. It is well-known that the Mainlander Chinese and the Westerners constantly mock our lightweight grasp of Mandarin and English, and, for those doing business in China, they are taking Mandarin lessons to make up for their linguistic lack. Beneath these foreign mockery is the sneering at our cultural ignorance, superficiality, and philistinism. Further, if the ability to speak Mandarin is such an economic asset, why do our education policies prevent our non-Chinese compatriots from learning it? And should Singaporeans be learning Mandarin just so we can ‘bring value-add to China’?

Such vulgar economic justifications for ‘national survival’, for learning languages, for effacing cultures.

Whatever the material benefits I might reap by way of Singapore’s ‘economic usefulness’ to the rest of the world, I derive no dignity in being treated as a cog in a machine, as a means to an end. I would gladly trade, pardon the pun, GDP growth with the ability to speak my native language (it is neither English nor Mandarin) even if it is the most economically unviable language in the world. For that matter, I would be proud to be a Singaporean even if it is the poorest country there is around. What consolation does it bring, to be able to speak to 1.3 billion Chinese all over China if I cannot even engage in a proper conversation with my own family?

Whatever the material benefits I might reap by way of Singapore’s ‘economic usefulness’ to the rest of the world, I derive no dignity in being treated as a cog in a machine, as a means to an end. I would gladly trade, pardon the pun, GDP growth with the ability to speak my native language (it is neither English nor Mandarin) even if it is the most economically unviable language in the world. For that matter, I would be proud to be a Singaporean even if it is the poorest country there is around. What consolation does it bring, to be able to speak to 1.3 billion Chinese all over China if I cannot even engage in a proper conversation with my own family?That is not to say we should not have encouraged the learning of Mandarin. But it certainly could have been implemented in a less mechanistic manner, and for less utilitarian reasons. It is for these very reasons that we do not want to, or we are unable to, appreciate the value of a language and the beauty inherent in all languages, that exist beyond the jargon and jarring phrases of multinational companies and Internet data banks and global financial-speak.

The choice of languages learnt need neither be government-sanctioned nor mutually-exclusive. Contrary to what the government and the media would like us to think, we are not the only country that adopts a bilingual policy. But compared to other such countries, we are far from being as successful. Learning from them, we might realize that mastering Mandarin need not have come at the expense of our ancestral tongues. Our lack of fluency in multiple languages is not just due to biological limitations (which is far from being a fact). Ill-conceived, flip-flopping government policies and crass economic rationale for learning (or un-learning) languages have contributed to this predicament too.

In two generations Mandarin would be our mother tongue, proclaims MM Lee proudly. But with our appalling level of proficiency in Mandarin, it is not hard to foresee how much and what kind of a ‘mother tongue’ it is going to be. It will probably not be much.

Is the sole value of a language its ‘usefulness’? I don’t think so. On the one hand, use-value is subjective, personal, and should not be decided for me by, of all things, the state. On the parallel, the value of language is in language itself. Languages do not appear out of thin air – we human beings create them, keep them alive, and they live for a simple reason – above being basic tools of communication, they are expressions of our emotions, our humanness. Expressions that, like culture and the arts, live outside the world of money.

Is the sole value of a language its ‘usefulness’? I don’t think so. On the one hand, use-value is subjective, personal, and should not be decided for me by, of all things, the state. On the parallel, the value of language is in language itself. Languages do not appear out of thin air – we human beings create them, keep them alive, and they live for a simple reason – above being basic tools of communication, they are expressions of our emotions, our humanness. Expressions that, like culture and the arts, live outside the world of money.We would have been better-off leaving our language habits alone, and letting our ‘adulterated Hokkien-Teochew’ languages evolve on their own. And why not? Languages, like cultures, are living things and they evolve all the time. And over time, our aesthetic sensibilities are honed along with our constant polishing of our tongues, and from where the beauty and poetry in the language emerge. This is true for all languages, from the first grunt in the dark cave eons ago, to the final stanza in the gilded library just now. And why, our Singlish vernacular might one day become high language too, with its inimitable trove of stories and sonnets. If only we would let it, and let our local poets light the way.

But of course, such frivolous pursuits have no place in a country where economic necessity and cultural cringe must prevail. While the sun of the British empire might have set, and the Middle Kingdom’s might yet arise, it seems as long as the ruling regime’s socio-economic ideologies persist blindingly, Singaporeans will always remain colonial subjects, servants to capital.

The way we have gone about picking ‘winning’ languages and experimenting with them as one would in a laboratory, it is what kills language. But not only that – as fellow TOC contributor Deng Chao noted recently, what is wiped out is more than our Teochew, Hokkien, Cantonese, and Hainanese languages. Gone with them would be the irreplaceable and age-old cultural treasures of folklore, poetry, aphorisms and histories, riches that are later infused with the tropical air of the Straits Settlement – a natural confluence of cultures. What is wiped out will be life itself, supplanted by the mediocre, the vulgar and the kitsch.

One day I might become a grandparent too, but what would the world be like then? I do not want to punt on the vagaries of the market or the flow of global finance. I certainly do not want to be enslaved by them. Small as Singapore is, there nonetheless are things that do not and cannot have a price tag. The ability and the freedom to speak, for instance. Invaluable things.

Am I romanticizing the village?

But how did the village come to be something pejorative in the Singaporean imagination?

What kind of a city are we still building anyway?

What kind of a city are we still building anyway?Looking at my grandparents, I do wonder what their Singaporean world has been like, for them to one morning find themselves strangers in their own land, unable to be understood and unable to understand, the foreign chatter on the streets, and recounting life stories in a voice whose sweetness their loved ones would never know.

And how much are Singaporeans and our nation, for all our economic growth and material riches the poorer for it, living on benighted money, leaving our history behind.

-

Make mandarin compulsory for all

Friday, 21 August 2009, 10:50 pm | 1,480 views

Imran Ahmed

Immigration into Singapore has become a hot button issue among ‘born and bred’ Singaporeans.

Immigration into Singapore has become a hot button issue among ‘born and bred’ Singaporeans.As typically happens during recessions, there is a sense that ‘foreign talent’ is taking away jobs from indigenous Singaporeans. However, the debate is not always restricted to the economic sphere and often slips into the realm of race and ethnicity.

Race and ethnicity are sensitive issues here in Singapore. Government policies are implemented with a focus on increasing the ‘common space’ and fostering a tolerant and multi-cultural environment.

Citizens can only attend Singaporean schools where the curriculum is tightly controlled. International schools with their own individual courses of study are the preserve of the expatriate population. (See here)Government subsidized housing is assigned on the basis of ‘race’ to ensure that ethnic enclaves are not formed. Public holidays are allocated to the various communities as a result of which all Singaporeans celebrate Christmas, Hari Raya (Eid), Deepavali and Chinese New Year as public holidays. An individual’s race is even mentioned in his identity card (and yes my race is Pakistani!).

Foreigners who decide to make Singapore their home take the form of those who have ‘Permanent Resident‘ (PR) status and those who are naturalized Singapore citizens. Male children of all citizens must participate in the military for two years (National Service) under the Enlistment Act. While it is optional for male children of PRs, applications for Singapore citizenship from PR kids who did not partake in National Service are not entertained.

Many perceive the recent wave of immigrants, mainly from the People’s Republic of China and India, as being ‘opportunists’ who have a limited commitment to Singapore. Some believe they are only here to take advantage of government subsidies, especially housing grants and baby bonuses. (To address Singapore’s problem of an ageing population cash subsidies and tax credits are provided by the government as inducements to citizens to have babies.)

Additionally, it is commonly thought the new immigrants have scant regard for the rules which have slowly transformed ‘Singapore Inc.’ into a powerful brand. Many have imported social habits and customs (e.g. littering, spitting) which Singaporeans have painstakingly moved away from during the last four decades.

Language is another contentious issue. Singapore has four official languages (Mandarin, Malay, Tamil and English) but everyone learns and speaks English (see also ‘Singlish‘). Many of the fresh Chinese immigrants speak only Mandarin . This irks those Singaporeans who rely on English as the lingua franca of the island as many do not speak Mandarin. I do not wish to pontificate about the pros and cons of immigration as a necessity for maintaining economic growth and, hence, social stability in the island. I will leave that to the country’s founding father, Lee Kuan Yew, who can argue the case much more persuasively than me. (He does have a track record of delivering results which any corporate or political leader can only dream off!)

What I do wish to say is that the issue of integrating Singapore’s diverse population is more than just about making certain everyone can speak English.

It is about the ability to speak Mandarin in a Chinese society.

The teaching of Mandarin must be made compulsory for all Singaporeans, irrespective of their race.

The academic curriculum should be revised to ensure that Singapore’s kids are functionally fluent in three languages: English, Mandarin, and their mother tongue (Malay or Tamil).

Some may suggest that such an action can be deemed to be domineering by the majority race. Or whether Singapore’s already overburdened students can manage another serious subject.

Learning Mandarin is a practical matter and one that should be motivated by self-interest. If I could speak Mandarin my employability and market value will increase tremendously. The nature of jobs and occupations available to me multiply exponentially. These jobs may range from manufacturing concerns that have production facilities in China to entities trying to break into the Chinese market for goods and services.

Can a non-Mandarin speaker in Singapore truly integrate into Singaporean society? Despite the role of English as Singapore’s universal language an English speaker (like me) will always face limitations. The idea is not to supplant the supremacy of English but to take integration of all races in Singapore to the next level.

As for schoolchildren and whether they can mentally handle the stress of another major subject, examples from other parts of the world suggest that it is reasonable to assume that three languages can be taught at school.

It is not unusual for small nations to be multi-lingual. Most residents of the Netherlands, Belgium and Switzerland speak three languages. To be sure, the national curriculum will need to be adequately adjusted to ensure that space is created for teaching Mandarin. A major change in the curriculum cannot happen overnight and should be preceded by adequate research and debate.

Making the next generation of Singaporeans tri-lingual will increase social cohesion among all races and is an idea whose time has come. Ethnic and religious fault lines will decrease as inter-ethnic communication increases further. A small globally integrated economy like Singapore will reap the added bonus of enhancing the country’s existing competitive advantages in trade and the service sector by catering more fully to the ever growing China market.

Our neighbours have got this one right – Malaysians of all races study Malay from their first day at school. Is it finally time for Singapore to learn a trick from its old partner and rival?

-

wha lau, so lor sor, the govt need not mandate the speaking of languages and forgo dialect, they never said you cannot speak dialect...so what is the problem here, beside, knowing Mandarin is a plus plus for us doing business with Chinese. China Chinese are very happy to see other races able to speak mandarin, today, alots of my young malay and indian frens can speak Mandarin very well. It is sure a big advantage for them.

In fact in taiwan, hokkien is a language, not a dialect, people read han character and pronounced it in hokkien. And even our MM or PM also speak Hokkien or teochew at some point of their speeches, like Mee Siam Mai hum...

-

Singapore: Multiculturalism or the melting pot?

Monday, 20 July 2009, 11:49 am | 2,595 views

Announcement:

Chief Editor of TOC, Choo Zheng Xi, will be leaving for New York University on the 27th of July. He’ll be in NYU to pursue his masters degree in law. As such, he’ll be stepping down as Chief Editor and he’ll also be leaving TOC. Andrew Loh will assume the Chief Editor position in the meantime.Gerald Giam

With growing immigration from a more diverse spread of countries, will Singapore start seeing a dilution of our national identity as a result of immigrants insisting on their own cultural practices, even in the public sphere?

Last week, Straits Times reader Amy Loh wrote to the paper expressing her disquiet about the government’s emphasis on the need to speak Mandarin. This, she said, could be perceived as a clear signal to encourage residents of mainland China origin to choose to continue speaking only Chinese. She cited examples of how almost all new shop signs in Geylang are in Chinese only, fast turning this into a Chinese enclave.

Last week, Straits Times reader Amy Loh wrote to the paper expressing her disquiet about the government’s emphasis on the need to speak Mandarin. This, she said, could be perceived as a clear signal to encourage residents of mainland China origin to choose to continue speaking only Chinese. She cited examples of how almost all new shop signs in Geylang are in Chinese only, fast turning this into a Chinese enclave.In response, the Straits Times in an editorial slammed Ms Loh as being “xenophobic”, pointing to economically vibrant cities like London and Sydney as evidence that “recruiting foreigners” has brought great benefits to those cities. The paper went on to explain that the Geylang shop signs were in only Chinese for “purely commercial reasons”, as if that were an excuse for their cultural insensitivity.

This exchange raises another more important issue that Singapore, with its growing diversity and immigrant population, needs to start dealing with: The issue of multiculturalism versus a melting pot social make-up of our country.

Multiculturalism can be defined as a demographic make-up of a country where various cultural divisions are accepted for the sake of diversity.

A melting pot, on the other hand, is a society where all of the people blend together to form one basic cultural norm based on the dominant culture.

Countries like Canada and Australia have often taken pride in their practice of multiculturalism. The melting pot is often used to describe the US, where past generations of immigrants supposedly became successful by shedding their historical cultural identities and adopting the ways of their new country.

The Singapore model

The practice in Singapore has been rather mixed.

During the days of colonial rule, the British were happy to segregate immigrant races into different living quarters in the city, ostensibly in order to divide and rule the place more easily.

In the 1960s, then-Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew actively promoted the concept of a “Malaysian Malaysia”, as part of his attempt to ensure that Singapore Chinese were not disadvantaged by a political system that placed Malay rights above those of other races.

In 1989, the HDB introduced the Ethnic Integration Policy, under which the major races each have a representative quota of homes for them in a housing block. Once that limit has been reached, no further sale of HDB flats to that ethnic group will be allowed. The government claims that this is to prevent racial enclaves from forming.

During the tudung affair of 2002, MOE suspended two primary schoolgirls for insisting on attending school with their Muslim headscarves. Hawazi Daipi, the ministry’s parliamentary secretary, said that ”schools represent a precious common space, where all young Singaporeans wear school uniforms, as a daily reminder of the need to stand together as citizens, regardless of race, religion and social status”.

Backsliding towards a segregated society

Despite this apparent commitment to making Singapore a melting pot, there are examples of how the government has been promoting multiculturalism instead.

The Education Ministry continues to insist on its Mother Tongue policy in schools, whereby Chinese, Malay and Tamil Singaporeans are required to learn the language of their own ethnic group as a second language in schools. Thus Chinese Singaporeans have no choice but to learn Chinese, even if say their parents are Peranakan and don’t speak a word of Mandarin. Similarly, Malays do not have an option to learn Chinese to the exclusion of Malay.

The Speak Mandarin campaign started out as an attempt to get Chinese dialect-speaking Singaporeans to switch to using Mandarin. Over the years, it has morphed into a campaign to get English speaking Chinese Singaporeans to use Mandarin in daily conversations. Government leaders seemed oblivious to the grumblings among many Malays and other minorities about the blatant promotion of one culture over all the others.

“Ethnic self-help groups” like Mendaki, CDAC, Sinda and Eurasian Association have been formed to provide social services separately to Chinese, Malays, Indians and Eurasians.

Then there was the introduction of Special Assistance Plan (SAP) schools, which Mr Lee Kuan Yew sent his children to attend. SAP schools are given extra resources to nurture a generation of Chinese Singaporeans who are well versed in the Chinese language and culture. Again, nevermind the disquiet on the Malay and Indian ground.

Fast forward to last week, when the Straits Times all but condoned the use of Chinese-only shop signs in Geylang. Is our country sliding more and more towards a social model where it is acceptable for ghettoes of different races and people of different national origins to develop?

Many Singaporeans, and not just racial minorities, have expressed their irritation at service staff who are only able to converse in Chinese and not English, the de facto lingua franca of today’s Singapore.

With growing immigration from a more diverse spread of countries, will Singapore start seeing a dilution of our national identity as a result of immigrants insisting on their own cultural practices, even in the public sphere?

I hope not. Our nation may be young, but we have built up elements of a culture that is somewhat unique to Singapore — our local food, Singlish, a commitment to meritocracy to name a few. I welcome new immigrants who can contribute to Singapore. But I expect these immigrants to conform to Singaporean cultural norms rather than that of their country of origin. They should not think that they can simply continue to live and speak like they did back home, especially when interacting with Singaporeans.

As for local born Singaporeans, there is also a danger of our ethnic backgrounds taking precedence over our Singaporean identity. Chinese Singaporeans in particular need to be reminded that Singapore is not a Chinese country, even if their race might make up the largest proportion of the population.

Choosing the right model

I suppose there is no right or wrong in choosing multiculturalism or the melting pot. Different societies have tried both models, with varying degrees of success. Each nation will need to choose which one to emphasise more, depending on their unique circumstances.

My view is that Singapore needs to be more of a melting pot. This celebrates our commonalties rather than our differences. However this would necessitate giving up some aspects of our individual cultures, which some from the dominant culture may be loathe to surrender. But on the whole, I believe our society and culture will be stronger, more peaceful and more resilient if we emphasise our Singaporean-ness more than our Malay-ness or Chinese-ness

-

A response to MM Lee’s private secretary on dialects

Saturday, 7 March 2009, 2:24 pm | 6,847 views

Deng Chao

Recognition of our heritage and respect for diversity are not ignorance

I write in response to the Straits Times Forum Letter “Foolish to advocate the learning of dialects”, dated 7 March 2009, by Chee Hong Tat, Principal Private Secretary to the Minister Mentor.

I write in response to the Straits Times Forum Letter “Foolish to advocate the learning of dialects”, dated 7 March 2009, by Chee Hong Tat, Principal Private Secretary to the Minister Mentor.In his letter, Mr Chee argued that it is foolish to advocate the use of Chinese dialects as this threatens the effectiveness of Singapore’s bilingual policy. He also asserted that Mandarin is the mother-tongue of all Chinese.

Mr Chee is wrong on all counts.

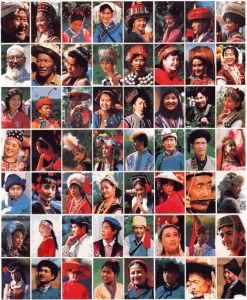

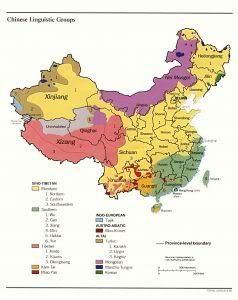

Firstly, the Chinese dialects which he refers to are rightfully languages. Spoken Chinese is distinguished by a high level of internal diversity. There are between six and twelve main regional groups of Chinese (depending on classification scheme). The key language groups include Wu (90 million speakers), Min (70 million) and Cantonese (or Yue) (70 million). Minnan (the southern branch of Min) includes also Hokkien, Teochew and Hainanese.

These Chinese languages are mostly mutually unintelligible tongues. They are roughly parallel to English, Dutch, Swedish, and so on among the Germanic group of the Indo-European language family. Within each Chinese language are supposedly more or less mutually intelligible dialects. For example, Cantonese has its Canton, Taishan, and other dialects, while Minnan has its Amoy, Taiwan, and other dialects. This is just like how English may be subdivided into its Cockney, Boston, Toronto, Texas, Cambridge, Melbourne, and other varieties. . (Source: Victor H. Mair, “What Is a Chinese ‘Dialect/Topolect?” Sino-Platonic Papers, 29 [September, 1991])

Our government has wrongly classified Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese, Hainanese etc as dialects of Mandarin. “Dialect” implies regional variation of a common language. However, the Chinese languages listed above are mostly mutually unintelligible. Fangyan (方言), the term used by the Chinese to classify their languages, does not correspond to the English term “dialect”. Fangyan may be translated as “regional language”. Fangyan was also the term used during imperial China in reference to non-Chinese languages, including Korean, Mongolian, Manchu, Vietnamese, and Japanese, and during the Qing dynasty, the Western languages. linguists and experts have in many studies found the southern Chinese languages to be distinct and unique from Mandarin. (Jean DeBernardi, “Linguistic Nationalism: The Case of Southern Min” Sino-Platonic Papers, 25 [August, 1991])

Using the same written script do not make the various Chinese languages dialects, just as English, French, Spanish and German, while using the same alphabetical system of writing, are clearly distinct languages.

Clear difference between written and spoken forms

Linguists have demonstrated that there are clear differences between the spoken and the written forms of a language. Moreover, unlike the Western languages the Chinese written characters are based on pictographs or ideograms and do not reflect the phonetic pronunciation of its speech. Hence while the Chinese have historically shared the same written script, people from the different regions have orally expressed the written text in their own tongues without being right or wrong.

Secondly, Mandarin is only one member of the family of Chinese languages. It is based on the Beijing dialect, which is part of a larger group of North-Eastern and South-Western languages. Historically it is known to other Chinese as Guanhua (官è¯�, i.e. official language. Hence the term “Mandarin”) or Beifanghua (北方è¯�, language of the northerners). The forefathers of most Singaporean Chinese were from the far south. They speak only Cantonese, Hokkien, Teochew, Hainanese etc, while the Peranakans speak Baba Malay, but remain uniquely Chinese in their customs. Mandarin is by no stretch of our imagination, our mother tongue.

The Beijing form of Mandarin was only chosen to be the standard form of spoken Chinese through a ballot in China in 1913, during which the Cantonese language lost only by three votes. The Chinese national language campaign at that time was modeled after the Japanese one. The Japanese only sought to standardize its language based on the Tokyo form, without intending to eradicate the regional languages. However the Chinese sought to establish Mandarin as the national language with the intent of eliminating the regional languages. (Source)

Thirdly, the southern Chinese languages are bridges, and not obstacles to the affirming of our cultural ties with China and the learning of Mandarin. The southern Chinese languages are not pidgin Mandarin as some have deliberately attempted to portray. In fact Chinese language experts have identified some of them, such as Cantonese, Teochew, to be “fossilized languages” as they contain oral and written elements of Middle Chinese (å�¤æ¼¢èªž) preserved since the Tang dynasty (618-907AD). Reading of ancient Chinese poems and verses in these languages has also been found to be much smoother than when using Mandarin as the southern Chinese languages have about eight to nine tones, whereas Mandarin only has four.

Heritage being lost in Singapore

An abundance of knowledge of Chinese traditions, values and history is contained in the oral and written embodiments of these southern Chinese languages, such as surviving literature, operas and stories. Sadly, the chain of passing down this heritage is being lost rapidly in Singapore. Familiarity with the richness of the past had given the first generations of Singaporean Chinese the advantage of appreciating Chinese culture and learning Mandarin. Cut off from our roots by the government’s clampdown on the southern Chinese languages, many young Singaporeans today have little affinity with the endless list of idioms they are forced to memorise. For our parents, they were meaningful as these idioms were spoken to them in their mother-tongues through stories by their parents, and usage in daily lives.

Moreover, many Singaporeans who have worked with other Chinese can testify to the economic and non-economic advantages of communicating with their counterparts in their native language, such Cantonese in Hong Kong, Minnan / Hokkien in Taiwan, Shanghainese in Shanghai, over the use of Mandarin.

The deliberate classification of the southern Chinese languages as dialects is a socio-political attempt to degrade them as second-class. The attempt to eradicate them is narrow-minded and short-sighted.

Singapore’s bilingual policy has certainly offered us some advantages. However, it is limited by its strait-jacket CMIO (Chinese, Malay Indian, Others) racial model – besides English, Chinese to speak Mandarin, Malay to speak Malay, Indians to speak Tamil, and Others – one of the above. The CMIO model in turn is a legacy of the colonial British government’s divide and rule strategy, which was developed on a poorly-conceived and out-dated 19th century classification of people by race. As a result of the official failure to think beyond the CMIO box, most Singaporeans are sadly ignorant that the Malay community have more to offer through its close interactions with the Bugis, Minangkabau and Javanese, while the Indian community has the wealth of the Tamils, the Malayalees, the Sikhs, and other groups to share.

Ignorance and bigotry are foolishness. Recognition of the heritage of our forefathers, and respect for diversity of our nation are not.

(More information on the Chinese languages can be found on my Facebook group http://www.facebook.com/home.php?#/group.php?gid=42688422747)

-

The language of our forefathers – are we missing something?

Wednesday, 28 February 2007, 1:39 am | 1,438 views

By Zyberzitizen

By ZyberzitizenIt’s been decades since we were urged to “Speak Mandarin” by the government, instead of speaking our dialects. I’ve never agreed with this policy. This is because I find our dialects fascinating and beautiful. But more than that, my dialect reflect my ‘origin’. It’s a bridge to where my parents and my grandparents came from.

Teochew has a special place in my heart. I remember when I was just a child, Dad would tell us stories in this dialect. The many idioms and phrases and folk songs which are peculiar to the Teochews always made me smile – and even cry.

My uncles are the ones who have really ‘mastered’ the language. Mom calls theirs ‘Pure Teochew’, which to me can be quite indiscernible because they are “so cheem”. But that is why it fascinates me. There is a certain melody or flow to the language and sometimes you do not really have to understand the words to get what is being said.

It is the same with the other dialects in our country – be it Hokkien, Cantonese, Hakka, or Hainanese.

The “speak Mandarin” campaign

The “speak Mandarin” campaignThe “Speak Mandarin” campaign has sadly and unfortunately eroded the use of such dialects – especially among younger Singaporeans. There seems to be a lack of “rootedness” to their language. But is this important?

With language (dialects) comes your sense of identity, community, belongingness and uniqueness. Indeed, belonging to a particular dialect group allows you to keep in touch with its culture, customs and traditions.

These are the things which define who you are in the community.

And the dialect is the conduit, if you like, of these customs, culture and traditions. They are the oral history of a people. Such languages fill in the missing parts of written history of our people. And history too plays a part in rooting us, giving us a sense of identity.

There is no doubt that when you hear your own dialect being spoken, it is a markedly different feeling than hearing mandarin or English being spoken.

Separate dialects = segregation?

The question of course is: Does belonging to separate dialect groups prevent us from assimilating into “One People, One Nation, One Singapore”, which seems to be the government’s concern?

My answer would be no. We are already different and diverse – ethnically, culturally, individually. Also, we all have different life experiences. What we should be doing is to celebrate our diversity – whether it is language, or culture or traditions – instead of trying to “keep it out of sight and out of mind” in the hope that a “Speak Mandarin” campaign will create some sort of new “unity” among our different set of people under a new “one language”.

We can be diverse and be united at the same time.

Diversity is our strength – and it should not be seen as a ‘weak link’. “Sameness” does not necessarily mean “unity”. Indeed, “sameness” is uninspiring, it does not add to the vitality or vibrancy of life. Thus, I have always found it immensely regrettable that the government has embarked on the purposeful but artificial promotion of “one common language” – namely, Mandarin.And this has been done to devastating effect, in my opinion. TV programmes, radio shows, even Chinese cultural festivals are celebrated in mandarin instead of the diverse indigenous languages we have here in Singapore.

Mandarin’s economic valueIt is argued that Mandarin is an economic necessity, in the same way that SM Goh recently promoted the learning of Arabic. With a booming China, Mandarin will no doubt become a very important language for global trade and business in the years to come.

But how many Singaporeans will be doing business with China?

Sure, there will be the businessmen who will need a decent capacity to speak and understand the language if they’re doing business in China or with China businessmen.

But how about your ordinary Singaporean? We are all not going to be doing business with China or with China businessmen, are we?

And is it a good thing to substitute our dialects for something else because of economic necessity?

There is a place for dialects

Do not get me wrong. I am not against the learning of Mandarin in our schools but I am of the opinion that Mandarin should not be artificially foisted on the general population at large either. I do believe that there is room for dialects in their various forms to be expressed and celebrated.

For example, we could have television programmes in the dialects of our people. This would, first of all, allow our older Singaporeans to know fully what is going on. Even my Mom has difficulty understanding the news in mandarin. I would guess that most older folks have no inkling about globalization.

Secondly, it would bring a certain refreshing dynamism and vibrancy to what is heard, seen and produced in many of our television channels. I have often wondered how reflective our programmes are in representing our diversity.

Thirdly, I would argue that it would also bring an immediate sense of “Singaporean-ness” to our people. There is nothing like hearing another of your “kinsman” speaking the same language. Haven’t we all felt this when we travel overseas and meet with fellow Singaporeans who speak the same way or the same language we do? I was in Europe once and met a fellow teochew Singaporean who was also there on holiday. Conversing with him in our common dialect was indeed emotional. It brought back feelings of kinship and identity which no amount of Singapore Shares ever will.

And is this not what we are trying to do – to create a sense of ‘rootedness’ for Singaporeans? Surely there is no better way to do this than by openly and proudly celebrating and allowing the expression of our ethnic languages – and the culture, traditions and customs that come with them as well?

Chinese New Year 2007There is a certain sense of “lack” during this Chinese New Year as I observed my relatives celebrate the New Year of the Pig or boar, if you like. I am not sure if Singaporeans out there also felt the same way. A lack of erm….authenticity, even festivity, about the New Year celebration and its associated meaning.

Are we missing something?

A friend recently remarked to me that Chinese New Year is getting to be rather ‘empty’ in Singapore. “There is no meaning nowadays. Everyone is worried about keeping their jobs, the GST, their children’s future, cost of living. What’s so special about Chinese New year now? Kids even speak either mandarin or English. What has happened to our dialects? The traditions and customs? What is Chinese New Year going to be like in the future with so many foreigners here? Even Chingay also must have foreigners performing for us.”

I can understand how he feels.

None of my younger nieces and nephews greeted their grandmother in dialect. It was either in Mandarin or English, which their grandma didn’t understand.

Another friend, who was doing her masters degree in London, expressed similar feelings. “It was strange. I felt more Chinese in London than when I am in Singapore. Chinese New Year there seem to be more festive and meaningful than it is in Singapore. Even with just a small group of Chinese friends there, we felt more kinship than we do when we’re back here.”

Being proud of our heritageWhile we spend time, effort and money in trying to integrate and assimilate our foreign friends into our Singaporean society, we should perhaps also spend equal or even greater amount of time, effort and money in making sure that we have a Singaporean identity too. In fact we do have a Singaporean identity. We just need to be proud of it and preserve it and celebrate it.

And I would suggest that we start with us being proud of who we are, where we came from and the roots of our existence. Take pride in our heritage. Rootedness begins with the sense of familiarity – of family, places, of culture, tradition and customs, of kinship and brotherhood or sisterhood. Rootedness is not borne out of the next spanking shopping centre or an artificial language imported and enforced. Rootedness certainly is not and will not be established with the state giving out economic shares or “progress packages”. Or even providing us with luxurious HDB flats.

Be proud of our dialects – the dialects which our forefathers, grandparents and parents were brought up in, the languages which keeps them, even today, connected to each other. The dialects which gives them a sense of identity, of kinship.

And I dream and hope for the day when I hear – once again – the dialects of my forefathers being proudly expressed once again – even on television programmes.

Is it a coincidence that our lack of identity coincides with the erosion of our ethnic dialects?

Imagine this: Imagine our schools teaching the young simple phrases of dialects which our forefathers used when they toiled under the sun, with the sweat on their backs in manual labour.

Now, isn’t that something worth keeping and passing down to our next generation?

Update: Students learn dialect to communicate with elderly (May 6, 2007)

-

Just be quick and sharp, what is TS trying to prove here?

-

Speaking dialects helps build rapport, even in business

Saturday, 21 March 2009, 8:47 pm | 1,958 views

Sng B C

Perhaps we may wish to consider the role a dialect plays in building rapport and leading to business opportunities.

I refer to the Straits Times article, “Mandarin drive starts in the home”, on March 18, 2009.

I refer to the Straits Times article, “Mandarin drive starts in the home”, on March 18, 2009. When I was in secondary school, I agreed wholeheartedly (presciently, it appears) with MM Lee’s statement that with Mandarin, “We can connect with the whole of China and its 1.3 billion people. Dialects will confine us to our original village or town or at most, the province of our ancestors”. I even took that line of reasoning one step further – I thought that with English, I could connect with the whole of the English-speaking world. Mandarin, I thought, would confine me to China and its 1.3 billion people – a large percentage of whom would eventually learn to speak English anyway.

Along the way I realised, however, that I could not build rapport easily with English speakers who did not speak English my way, the Singaporean way.

In university, I made it a point to brush up my Mandarin. However, I discovered that I still could not build rapport easily with Mandarin speakers who did not speak Mandarin my way, the Singaporean way.

For that matter, many Mandarin speakers in China find it difficult to understand the Mandarin spoken by people from other provinces. Although the Chinese Government has made it mandatory for Mandarin to be taught in schools, Mandarin is still not the mother tongue for most Chinese – their hometown dialect is. Northerners find it hard to understand southerners and the Shanghainese often gleefully mix Shanghainese words and pronunciation into their Mandarin. Does this sound familiar?

Building rapport

Building rapport is the first step to developing the all-important Guanxi in China. Building rapport is about seeking common ground, about getting the other person to treat me as one of “Us” and not as “Others”. In China, it is prevalent for family-run SMEs to have one price for Us and another higher price for Others. It may be surprising for some that many Chinese do not consider the Chinese from other provinces as Us, but rather as Others. So whom will a Chinese consider as Us? Someone with a nexus to his hometown, perhaps. Someone who enjoys the same food and speaks the same dialect, perhaps.

We all like to feel like members of an elite fraternity, and sharing a common dialect, even if it does not open as many doors as a Masonic handshake, still does wonders in building rapport. Perhaps we may wish to consider the role a dialect plays in building rapport and leading to business opportunities. After all, as the Teochew say, “Ga ki nang, pa si bo xiang gan” (If you are one of Us, it does not matter even if we die for you).

We all like to feel like members of an elite fraternity, and sharing a common dialect, even if it does not open as many doors as a Masonic handshake, still does wonders in building rapport. Perhaps we may wish to consider the role a dialect plays in building rapport and leading to business opportunities. After all, as the Teochew say, “Ga ki nang, pa si bo xiang gan” (If you are one of Us, it does not matter even if we die for you).Just look at the facts – the Cantonese-speaking Hongkong-ers have made many successful investments in the predominantly Cantonese-speaking Pearl River Delta of southern Guangdong Province , but do not have investments of a similar scale in north-eastern Guangdong Province , which is predominantly Teochew-speaking. Similarly, the Hokkien-speaking Taiwanese have made many successful investments in predominantly Hokkien-speaking southern Fujian Province, but do not have investments of a similar scale in northern Fujian Province , where the Min Bei dialect (which is mutually unintelligible with Hokkien) is prevalent. Can Singaporeans, who have been trained to speak Mandarin and not dialects, boast of a similar presence and as many successes investing in China?

The Hokkien spoken in Singapore is not the same as the Hokkien spoken in Taiwan or in Fujian Province . Nevertheless, speaking a variant of the dialect is often sufficient to build rapport – after all, it is a standing joke in Fujian Province that every village speaks a different variant of Hokkien from the next village across the mountain.

Leveraging on dialects

One does not have to be extremely proficient in a dialect to build rapport. From personal experience, it is sufficient to be able to conduct a simple conversation in a dialect to draw attention to the commonality of the ancestral homeland. Further negotiations can be carried out in Mandarin. I have oftentimes been able to leverage on my dialect to obtain better prices from Hokkien vendors than my non-Hokkien Chinese counterparts.

Furthermore, the use of dialects is not restricted to China. The Chinese Diaspora began long before Mandarin became the official dialect in China . As such, there are approximately 30 million Overseas Chinese, originally from Guangdong, Fujian and Hainan provinces , who may not be able to communicate fluently in Mandarin. It would not be a far stretch to assume that it would be easier to build rapport with an Overseas Chinese by speaking to him in his dialect, rather than struggling to carry on a conversation in Mandarin. This might prove difficult in two generations’ time, if, as MM Lee predicts, “Mandarin will become our mother tongue”.

With regard to Mr. Chee Hong Tat’s comment that “it would be stupid… to advocate the learning of dialects, which must be at the expense of English and Mandarin”, I would like to introduce him to some Malaysian Chinese friends of mine. Speak to a Malaysian Chinese, and chances are, she can speak English, Mandarin, Malay, Cantonese and Hokkien well enough to carry on a conversation in all of the abovementioned languages. As MM Lee rightly pointed out, English and Mandarin are two “manifestly different languages”. The dialects that we are referring to, however, are merely spoken variants of the Chinese language. Surely, learning to speak a dialect must be easier than to learn Malay along with English and Mandarin?

I agree with Ong Siew Chey’s letter on March 19, 2009 that “in spite of our claim of being bilingual, some of us are actually non-lingual, hovering between Singlish and substandard Mandarin.” The Speak Mandarin Campaign started 30 years ago. If Singaporeans, after 30 years of the Speak Mandarin Campaign, are still “non-lingual”, can anyone be certain that not speaking dialects is really the cure for “non-lingualism”?

In 2005, I had the pleasure of meeting Mr. Robert Kuok, the “Sugar King of Asia”, together with a delegation of NUS students. Mr. Kuok (then a sprightly 82 year-old multi-billionaire) took the effort to greet us individually when we first met. Upon hearing our surnames, he would first make guesses at our dialect groups, and greet us with a few words in each of our own dialects. This left a deep impression on me, and I hope that one day, with proper training, my “5GB” brain would be able to replicate that feat.

However, I understand that I should not be too hard on myself if I cannot learn to speak several dialects. After all, Mr. Robert Kuok’s unique. He’s Malaysian.

-

it lighten up my day - but eat in moderation

it lighten up my day - but eat in moderation -

ok, that quick and sharp, i will eat moderately, beside, i have to watch my shape. So, be it curry pao, meat bao, sotong balls etc etc ...we can never forget that we are mutlilingual and cultures.

-

for myself only - it spice up my day, when i managed to eat it at the right time, place.

for myself only - it spice up my day, when i managed to eat it at the right time, place.

cheers to myself

-

root power

-

Revenge of the potato eater: Speak English to work here

DURING my full-time national service, someone once asked me in English: "You eat potato?"

What a strange question. I wasn't even eating anything at the time.

My tuber-fixated interrogator repeated the query, insisting on an answer: "You eat potato?" Hasn't everyone eaten a potato at least once in his or her life? So I said: "Yah, I eat potato.

Don't you?"

"You eat potato," he repeated with bemusement, as if I had confessed to masturbation.

"I eat potato."

"You eat potato."

"I eat potato."

This went on for a while until the person was satisfied that I had indeed confirmed that I ate potatoes and left to tell everyone very loudly that I said I ate potatoes like it was the funniest thing in the world.

It wasn't until later when I found out that to say a Chinese Singaporean "eats potatoes" is to mock him for being so Westernised that he speaks English rather than Mandarin or other Chinese dialects.

I guess the assumption here is that the potato represents Western food, like the fries in a McDonald's meal.

Ironically, when I was asked the potato question, the first thing I thought of was the potatoes in my mother's curry - not a very Western dish.

So it never occurred to me that "eating potatoes" had anything to do with my language preference.

That was when I realised that being an English-speaking Chinese Singaporean, I was in the minority.

"Big" minority

But we are a big enough minority - or big enough spenders - that last week, the Government announced a new rule that will hopefully reverse the trend of a growing number of service workers recruited from abroad who can't speak English to customers like me.

From the third quarter of next year, new foreign workers have to pass an English test before they can get a work permit as a skilled worker.

We felt vindicated when Minister Mentor Lee Kuan Yew admitted that Chinese language has been wrongly taught in our schools for 40 years, turning Chinese Singaporeans like me off our own mother tongue.

Many potato-eating Singaporeans have treated MM Lee's mea culpa as licence to openly condemn the Government's bilingual education policy for messing with our lives and the lives of our children.

Some complain about how they were forced to emigrate because of the policy. Hey, at least they had the option to emigrate. No other country would take me.

So it's almost fitting that foreigners now have to learn English to work in our country. Why should we be the only ones to suffer?

For that, I do not mind being called a "potato eater". Suddenly, I feel like curry.

-

Originally posted by angel7030:

ok, that quick and sharp, i will eat moderately, beside, i have to watch my shape. So, be it curry pao, meat bao, sotong balls etc etc ...we can never forget that we are mutlilingual and cultures.

Why will a Taiwanese 'hum' be choosy - when a "Banana or creature or chameleon is not important, as long as he holds the key" to unlock the Taiwanese 'hum' and release it into a realm of orgasmic pleasures that it needs as an "Attention Seeking Whore" ?Now the Taiwanese 'hum' will accept any curry that can give it the pao, or better if the meat is in the bao, with sotong balls to top the entire list to satisfy the hunger of a Taiwanese 'hum' looking of more attention as an "Attention Seeking Whore".

Originally posted by angel7030:root power

It confirms that the Taiwanese 'hum' will never cease until it gets full satisfaction - which the previous curry with the pao, or meat in the bao, and sotong balls remains insufficient.

Now it needs "a root" to complete the insatiable orgasmic needs of an "Attention Seeking Whore".

-

Originally posted by light 123:

Revenge of the potato eater: Speak English to work here

DURING my full-time national service, someone once asked me in English: "You eat potato?"

What a strange question. I wasn't even eating anything at the time.

My tuber-fixated interrogator repeated the query, insisting on an answer: "You eat potato?" Hasn't everyone eaten a potato at least once in his or her life? So I said: "Yah, I eat potato.

Don't you?"

"You eat potato," he repeated with bemusement, as if I had confessed to masturbation.

"I eat potato."

"You eat potato."

"I eat potato."

This went on for a while until the person was satisfied that I had indeed confirmed that I ate potatoes and left to tell everyone very loudly that I said I ate potatoes like it was the funniest thing in the world.

It wasn't until later when I found out that to say a Chinese Singaporean "eats potatoes" is to mock him for being so Westernised that he speaks English rather than Mandarin or other Chinese dialects.

I guess the assumption here is that the potato represents Western food, like the fries in a McDonald's meal.

Ironically, when I was asked the potato question, the first thing I thought of was the potatoes in my mother's curry - not a very Western dish.

So it never occurred to me that "eating potatoes" had anything to do with my language preference.

That was when I realised that being an English-speaking Chinese Singaporean, I was in the minority.

"Big" minority

But we are a big enough minority - or big enough spenders - that last week, the Government announced a new rule that will hopefully reverse the trend of a growing number of service workers recruited from abroad who can't speak English to customers like me.

From the third quarter of next year, new foreign workers have to pass an English test before they can get a work permit as a skilled worker.

We felt vindicated when Minister Mentor Lee Kuan Yew admitted that Chinese language has been wrongly taught in our schools for 40 years, turning Chinese Singaporeans like me off our own mother tongue.

Many potato-eating Singaporeans have treated MM Lee's mea culpa as licence to openly condemn the Government's bilingual education policy for messing with our lives and the lives of our children.

Some complain about how they were forced to emigrate because of the policy. Hey, at least they had the option to emigrate. No other country would take me.

So it's almost fitting that foreigners now have to learn English to work in our country. Why should we be the only ones to suffer?

For that, I do not mind being called a "potato eater". Suddenly, I feel like curry.

<!-- CONTENT : end --><!-- Google Analytics SSI BEGIN --><!-- Google Analytics Education --> <!-- Google Analytics Education --><!-- Google Analytics SSI END --><!-- GA SSI BEGIN --><!-- GA News --> <!-- GA News --><!-- GA SSI END --><!-- reader comment start --> <!-- story rating start -->

Nerds are nerds, what to do?thinking alway straight until they hit a lampost then wake up, me young young already know what is eat potatos, and when people asked me, you eat potatos, i said no, i eat Kan tan, chinese potatos ya

-

Originally posted by angel7030:

Nerds are nerds, what to do?thinking alway straight until they hit a lampost then wake up, me young young already know what is eat potatos, and when people asked me, you eat potatos, i said no, i eat Kan tan, chinese potatos ya

Do you think a nerd has the sufficient size root to satisfy the orgasmic need of a Taiwanese 'hum' as an "Attention Seeking Whore" ?Try the hard boiled "kan tan" and roll it over the tired out clitoris that you have been over using and you will get your orgasmic fix and go to sleep and stay out of trouble as an "Attention Seeking Whore".

-

ha ha ha

-

he he he ho ho ho...hi nerd

-

Somebody called my name?

I am meat bao.....although FireIce forced me to turn vegetarian.... (she banned me)

Anyways, those articles are wayyyyy too long.....man...how can you expect people to read all of them....please make executive summary next time....

I got tired after reading the first article....so I just want to comment and respond on the first one only....the others I dont know....

Hmm.....in my opinion.....even though Singapore has several races and ethnic groups, it is not abnormal or unusual to promote the language of the majority group.

If you see the countries of the world, there are lots of them, in fact I think most of them, are multi-ethnic. They use the language of the majority group, sometimes with absolute strictness (no other languages allowed), and sometimes with concurrent usage with other smaller languages.

I disagree very strongly that to promote "unity", then the way is to promote an external language which is not the base of any ethnic group, thus, it is "fair".

This kind of logic is infant logic.