What was life like in Singapore in emergency rule(1948-1960)

-

What was life like in Singapore under british emergency rule from 1948-1960?

-

Life could not have been better even as life was difficult during the times immediately after the end of WW-2 with the surrender of the Japanese.

The period of the Malayan Emergency from 1948 to 1960 was largely a Malayan experience, when the rural Chinese communities living in remote villages were all rounded up and placed in specially built camps that were guarded by the British Military.

Life in Singapore was not as harsh in that the British Special Branch was doing most of the battle with the Communists, with the battles fought discreetly in an urban city such as Singapore.

The British Special Branch - (equivalent to the present day ISD) - was doing most of the undercover investigative jobs, to ferret out the Communists, and to keep a lid on the spread of the calls for independence from the Crown Rule.

In Singapore, daily life continues, and the ruling Colonial Government had to face the growing call for independence throughout its colonies in Asia, and had to draw a fine line in sand for local political activists.

The daily tussles of the various Trade Unions with their Employers over a slew of grieviances - that will include wages, working hours, welfare benefits, and other benefits - were the main issues of the day.

Then there was the constant bickering between the Chief Minister and members of the varios political parties in how best to handle the breakout of trade unionism that brought daily strikes.

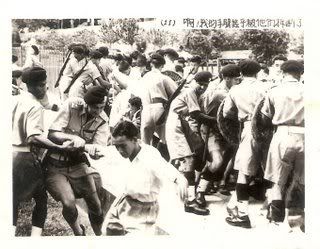

Student activism was rife and these include students from the Chinese Middle School as well as the socio-political activists from Nantah University.

Soon the strikes erupted into the infamous Hock Lee Bus Riots - which were later established was created by then Chief Minister Lim Yew Hock.

Life in Singapore was commerce and more commerce, with Singapore being called the "Suzie Wong" city for the many British Soldiers stationed in Peninsular Malaya and Singapore.

A report titled "British Legacies (2)" will provide an insight into the Life in Singapore during that period.

-

Originally posted by Atobe:

Life could not have been better even as life was difficult during the times immediately after the end of WW-2 with the surrender of the Japanese.

The period of the Malayan Emergency from 1948 to 1960 was largely a Malayan experience, when the rural Chinese communities living in remote villages were all rounded up and placed in specially built camps that were guarded by the British Military.

Life in Singapore was not as harsh in that the British Special Branch was doing most of the battle with the Communists, with the battles fought discreetly in an urban city such as Singapore.

The British Special Branch - (equivalent to the present day ISD) - was doing most of the undercover investigative jobs, to ferret out the Communists, and to keep a lid on the spread of the calls for independence from the Crown Rule.

In Singapore, daily life continues, and the ruling Colonial Government had to face the growing call for independence throughout its colonies in Asia, and had to draw a fine line in sand for local political activists.

The daily tussles of the various Trade Unions with their Employers over a slew of grieviances - that will include wages, working hours, welfare benefits, and other benefits - were the main issues of the day.

Then there was the constant bickering between the Chief Minister and members of the varios political parties in how best to handle the breakout of trade unionism that brought daily strikes.

Student activism was rife and these include students from the Chinese Middle School as well as the socio-political activists from Nantah University.

Soon the strikes erupted into the infamous Hock Lee Bus Riots - which were later established was created by then Chief Minister Lim Yew Hock.

Life in Singapore was commerce and more commerce, with Singapore being called the "Suzie Wong" city for the many British Soldiers stationed in Peninsular Malaya and Singapore.

A report titled "British Legacies (2)" will provide an insight into the Life in Singapore during that period.

Before i go furthur...when you say life could not be better, do you mean it as personal experience or a conclusion you got from reading historical text?

I just like to understand the source of your certainty that it was better.

-

how many of us here in this forum was born before 1945 and lived through 1948 - 1960 as a youth to tell what life was all about?

how many in this forum had to bring food to their children, take care of old parents during 1948 - 1960 and are alive to tell what life was all about as parents?

But just reading from history, there are something we can learn, and I had heard from some elders about some of the specific incidents, this is what I know:

1947 severe food shortage leading to record-low rice ration.

1948 state of emergency

1950 Maria Hertogh riots

1954 Chinese school students demonstrated against NS

1955 4 killed in Hock Lee bus riots

1956 Riots by pro communist Chinese school students when student union was closed

1956 River Valley High, first Chinese secondary school established by government

1961 Bukit Ho Swee fire

1947 many had not, or just arrived in Singapore, so low rice rationing was better than no rice. Life couldn't have been better.

1948 the angmoh didn't know which Chinese were communists and who were not, feeling was not good, especially from the look of some Chinese who din even passed grade 9, the equivalent to the current O level, but could become chenghu lang. After all, those working for the Jap or the Brits all the same.

1950 riots between Malay and angmoh didn't affect Chinese, thanks to the secret societies, 24, and the 08. But if your sons join them, your heart break.

When Chinese school students demonstrated against NS and the closing of students union, all who studied Chinese schools, the 是�是, could not find jobs in any government organisations, all kena work in the 98 行 in telok ayer street.

Finally, the River Valley Secondary School started, 立化, the feeling of being recognised as Chinese who could study our own language. The feeling couldn't have been better.

Bukit Ho Swee fire, could see fire from whole singapore, don't know how many thousands got no home, only the thak angmoh ce kia angmoh chu wan didn't feel anything, many said that fire was started by the government because they couldn't evict the slump. But, when they all moved to the HDB flat, life couldn't have been better.

Nobody could tell me how the parents survived and yet brought up their children, especially when they didn't speak english, LKY was too young to be scolded, and want to scold the angmoh government, didn't even know how to pronounce their names, their name got no abbreviation...hahaha

but people like my uncle in Singapore, who were born just after 1960, they had their good time, with 5cents, they had their once a week kok kok noodle, even during the 1964 riots, they got free bus ride home from primary school....

life couldn't have been better, then or now, it depends if you know how to enjoy life.

-

Firstly, there are no clear documented accounts of life during the period immediately when the war came to an end in Singapore, and in the NLB archives there are also little in terms of recorded voice or written history despite the publicity given.

Secondly, it is doubtful that anyone of the participants who can still type into prints in this Speaker's Corner would have lived through that period to express first hand the life experiences that transpired.

Thirdly, one will be surprised how much is still alive in the memories of those who are still around in their 60s to 80s despite their grey or white hairs, and the warmth that these elders will give when one shows interest in their memories.

Fourthly, the information that is offered is largely from my personal interests in understanding what life was truly about during and after the WW-2 in Singapore; and much has been discovered in my conversation with great-grand parents and the grand-parents before they passed on, parents, uncles and aunts, any old folks; and have these conversations corroborated with more conversations with the surviving old folks of that genre who belonged to my friends' families, and simple conversation with strangers from that generation.

Fifth, meshing the verbal accounts with whatever that can be extracted from prints in different books of that period - ranging from the arts, the living biographies, cuisines, culture, movies, and photo journals - one can build up a vivid picture of the dramatic flavors of that period.

WW-2 formally ended in Singapore, only in a second surrender ceremony held in Singapore on 12 September 1945, Admiral Lord Mountbatten accepted Japanese surrender in Singapore and witnessed the raising of the Union Jack at the Padang.

Life was hard during the war, when survival was living on a daily diet of tapioca and sweet potatoes that are easy to grow in small patches dug from broken cemented floors of urban dwellings, and the food made less boring by the culinary skills of the ingenious women folks despite the hardship and scarce commodities like salt, sugar and flour - (rice was unheard of).

Life immediately after the war ended was no less different but more tolerable with the hope of better things to come.

Life was seen to be better due to the fact that life is no longer as uncertain as during the Japanese Occupation - when one could be taken off the street for interrogation and worse simply for not bowing to a Japanese sentry on street duty.

The British Military administered Singapore until the arrival of the Civil Servants from the British Colonial Office, and with the rapid military efficiency in logistics, civilian supplies were quickly brought in from India where the military efforts were based to retake South-east Asia from the Japanese.

Even though supplies were limited at the early stage, limited supply of rice was better than the taste of tapioca and sweet potatoes being the staple for the last four bitter years of death, hunger, and uncertainty.

Could life have been worse in 1946 compared to the period living under Japanese Occupation ?

The defeat of South-east Asian Colonial Rule by the Japanese has been well documented, and its effects were also recorded to have opened the eyes of Asians that the heavy hand of the colonial rule by caucasians is not invincible.

The events ignited separate movements for independence from colonial rule that spread like wild fire across Asia - from India to Vietnam, from Indonesia to Burma.

The politics of Peninsular Malaya and Singapore were deliberately separated by the British Colonial Government, and the Emergency in Malaya was largely a Malayan affair to contain an invigorated guerilla movement for independence that was started by the Malayan Communist Party - who were previously armed and trained by the British to fight the Japanese Occupation.

The British Special Branch in Singapore was mindful of the possibility of the influence of Communist ideology in a large Chinese urban population in Singapore, many with personal ties still linked to families in China - now largely controlled by Mao Tse-tung, who will soon end the civil war with Chiang Kai-shek's Kuomintang.

The Emergency Rule was largely affecting the rural folks in Peninsular Malaya and did not touch on the lives of those living in Singapore.

Economic activity soon recovered through the vast opportunities available to the army of industrious merchants and entrepreneurs to re-stock and rebuild, and the humdrum of an urban city soon ran full steam to rebuild the private fortunes of the Lee's, the Tan's, the Chan's, the Kwek's, the Aw's, the Tang's - that were the household names of the 1950's before the PAP arrived on the political scene.

If not for the Japanese invasion into China, the outcome of the civil war between the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party – would have seen a different outcome for China. The events in South-east Asia would also have been different.

The civil war - between the Communist Party of China under Mao and Kuomintang under Chiang Kai-shek - was not settled until 10 December1949, when Chiang had to retreat from Chengdu to the island called Formosa (now known as Taiwan).

The Chinese in Singapore - and throughout South-east Asia - were involved in one form or another with the politics in China, and had given financial support to the party of their choice. Most South-east Asian Chinese had given their moral and financial support to Mao's CPC for the virtuous politics compared to the well know corruption and incompetencies of Chiang and his generals.

The vast amount of financial contributions from South-east Asian Chinese given to the different parties involved in China's civil war - during the period after the war - is testimony to the economic recovery soon after the Japanese surrender in 1945.

The British Civil Administration soon implemented policies to bring back normalcy to life in Singapore - providing public housing in the S.I.T. building program which is the forerunner to the HDB , education that recognised the importance of the different ethnic communities in Singapore, public security in a regular police force supplemented by a Volunteer Corp with oversight by the Special Branch.

Overall, the various public policies set by the British Colonial Government had continued to this day with little but necessary changes to meet new challenges and new circumstances - but with the essence remaining the same.

Was the Mariah Hertogh case all about “Race” or were the original causes distorted and twisted to suit politics of today ?

According to a research documented, the Mariah Hertogh riots was due largely "to the insensitive way the media handled religious and racial issues in Singapore, with the British Colonial Authorities failure to defuse an explosive situation when emotional reports appeared in local press of the custody battle accompanied by sensational media photographs of a Muslim girl in a Catholic convent.

As a result of this historic event, the Government of Singapore, upon independence in 1965, instituted legislation against racial discrimination."

Politics in the early 1950s were enthusiastically supported by Singaporeans and many shared ideals of basic human rights in freedom of assembly, open exchanges of ideas, open debates - all of which were very evident and so eloquently expressed by LKY in his representation of Trade Unions rights to the Colonial Government in the 1950s, and later when he represented Singapore's interests in the Federal Parliament in Kuala Lumpur.

What changed ?

Are Singaporeans less entitled to those lofty ideals of the 1950s now that Singapore is independent ?

Are Singaporeans more entitled to such lofty ideals only as part of a bigger country when merged with Malaysia ?

Is Singapore more vulnerable today then in the years immediately after WW-2 ?

Has Singapore become so vulnerable today - that we cannot enjoy the freedom of assembly and democratic politics of the First World that even the Israelis and the Swiss enjoy in their own set of even more challenging circumstances ?

In the 21st Century, is Singapore still facing the challenges of the 1950s ?

Has no progress been made after 52 years of LKY's influence and social moulding ?

Even Indonesia - in their own set of challenging economic, political, and security circumstances faced by over 100 Million citizens - have a more open political system than Singapore's 3.5 Million citizens.

-

My father say they led a relax life. Only city people like to fight here and there.